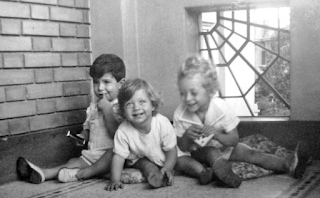

The Bivas children at the spiderweb building (Photo: A. Bivas)

The oldest photograph that Albert Bivas sent me was dated June 11, 1933—when his maternal grandparents held a groundbreaking ceremony for the spiderweb building. In the picture, Betty Bassan and Léon Bassan stand next to a foundation stone. Betty is tapping the stone with a hammer. Around them, a crowd of people are dressed in European-style clothes, while a large Egyptian man in a white galabiya is helping to hold the foundation stone.

The next photograph is from the inauguration of the finished building. A small group of men stand in front of the webbed balcony that, eight decades later, would lead to the room that I used as an office. In the picture, there are signs for the various groups that contributed to the construction: the contracting firm, whose name is Italian, and Schindler, the German company that installed the elevator.

Albert and his family had lived in that same ground-floor apartment. He was born in Cairo, in 1941, and after him his parents had four girls. The identical twins, Betty and Danièle, were born in 1944. In photographs, the baby twins are beautiful, with curly hair and enormous eyes, and in several images they sit on the balconies. The details of these scenes—the metal spiderwebs, the patterned floor tiling—are exactly the same as in photographs of my own twins.

Albert’s grandparents lived on the floor directly above. Like all of Albert’s known ancestors, they were Sephardic Jews who, at the end of the fifteenth century, fled the Inquisition in Spain and Portugal. They settled in Constantinople, which was welcoming to Jews at the time. Albert’s grandfather Léon was born in Turkey, but as a young man he moved to Egypt.

At the time, such a move was relatively easy, because Turkey and Egypt were both part of the Ottoman Empire. A number of Jewish families had moved during the late nineteenth century, when the opening of the Suez Canal created business opportunities in Egypt. For a while, Léon taught at a French-language school, and then he became an importer of supplies for tailors. In Cairo, he joined a vibrant community of Egyptian Jews. Some families had been in the city for centuries, and a number of Jewish activists had been prominent in the Egyptian-nationalist movement that resisted British imperialism in the early nineteen-hundreds.

For Léon, identity was many-sided. He and his wife communicated in Ladino, a form of Old Spanish that incorporated words from Hebrew, Turkish, Arabic, and other languages. It’s also known as Judeo-Spanish, because the tongue was carried across the Mediterranean and sustained for centuries by the Sephardic Jews who had been driven out of Spain. Léon also knew Turkish from childhood, and he learned Egyptian Arabic. He loved writing poetry and essays in French, which had been the language of his education.

None of his writings were published, but they were collected in journals preserved by the family. Léon’s voice is witty, curious, and intensely observant. He was an outsider who came to consider himself Egyptian, at a time when the country was full of such people—Jewish Egyptians, Greek Egyptians, Italian Egyptians. In Arabic, Cairenes refer to their country as “um al-duniya,” “the mother of the world,” and Léon describes the place as a melting pot. “The fashions of all the countries and all the times cross each other in Cairo,” he writes, in April, 1934. “It is a crossroads of all the races; you hear all the languages. And every person betrays his origin by the way he walks and by the way he is dressed.” He describes the “nervous” walk of the Europeans, who move quickly but say little. In contrast, l’autochtone—“the aborigine,” or local—walks slowly, to preserve his strength. But he isn’t silent. “He speaks loud and laughs very loud,” Léon writes. “He is poor like Job and nevertheless happy to live.”

In the journals, Léon takes pleasure in the organized chaos of the Cairo streets. He likes the professional female mourners who are hired for funerals and who, “in between their wailing, slip in some low-class jokes.” He also admires the beggars, especially the ones who are small-time scam artists—“the false blind, the false deaf, the people who have no arms but actually have hidden arms, the people who act like cripples but actually can run with their strong little legs as soon as the shawish [a junior police officer] is following them.” He gently mocks the discomfort that such figures inspire in Western residents, who have a tendency to label any irritation “the eleventh plague of Egypt.” Sometimes the eleventh plague is the beggars; at other times, it’s mosquitos. In the early thirties, the eleventh plague was revolutionary student activists. “These students, when they are demonstrating, imitate what people do in civilized countries,” Léon writes. “They break streetlamps, burn tramways, ransack shops, and knock off the hats of passersby while screaming in favor of this or against that.”

“We took one class about the history of France, and another class about the history of Egypt,” Albert said. “There were contradictions between these classes—sometimes we joked that we didn’t know if our ancestors were the Gauls or the pharaohs!” He continued, “The same as when we were doing Passover in Cairo, and we would read the story about how we were slaves in Egypt. And now we were here! But how can we have servants here, if we were slaves? As children, we were very amused by this.”

Albert’s father was a stockbroker who founded a textile factory, and the family was prosperous. They had servants to clean the apartment and to cook, and the doorman, an Upper Egyptian named Mohammed, doted on the children. The family parked their Citroën sedan in a garage in the garden. When Albert and I talked, he sketched out the layout of the building, and he confirmed that the spiderweb gate had been designed for automobiles. His family hadn’t needed a ramp to reach the street, since a sidewalk had yet to be built. I wished that I had had this piece of historical evidence when my neighbor confronted me about my construction project.

The strange little world of Albert’s family—the island in the Nile, the mixed languages, the spiderweb building, with its combination of Art Deco, classical, and Islamic architecture—began to seem increasingly fragile in the nineteen-forties. The neighborhood experienced frequent blackouts, as it did during the political turmoil of the Arab Spring, but in the forties the cause was war. In June, 1941, Léon Bassan wrote a poem titled “Black Out”:

Close your shutters and turn off the lights

There goes the happiness of our dear homes

There are lines going through the sky, of pirate airplanes

In Egypt, German and British forces fought at Al-Alamein, on the Mediterranean coast west of Alexandria, but Cairo was relatively unaffected. Many Egyptian nationalists were sympathetic to the Nazis because of their hatred of British imperialism. But, for an Egyptian Jew, the fear of Hitler was visceral, and the name often crops up in Léon’s poems:

Satan is Hitler himself

Göring is the angry tiger

Goebbels is the cursed snake

And Himmler the vulture walking toward the prey

One of Léon’s sisters had got married and moved to France. After the war, Léon learned that his sister had been sent to Auschwitz, where she died. He never mentioned the death to his grandchildren, although even as a young boy Albert could tell that something was changing in Cairo. Once, he went to the cinema with his father to see a French movie, and when a Jewish character appeared onscreen, people in the audience shouted, “Kill the Jew! Kill the Jew!” On November 29, 1947, after the United Nations passed a resolution calling for Palestine to be partitioned between Arabs and Jews, angry mobs gathered in downtown Cairo. Albert’s family was out in the Citroën, and his father, whose name was also Léon, yelled at the children to duck, in case people caught a glimpse of them in European dress.

Léon Bivas had named his textile company Albitex, after his only son, and his dream was that Albert would someday take over the business. But, in 1952, as protests against the Egyptian monarchy intensified, Léon Bivas sensed that the regime might be toppled. He took his wife and children to France that summer, with the expectation that they would return after things stabilized. In July, when Nasser and the other army men who became known as the Free Officers carried out their revolution, the Bivas family was living in Paris.

Albert’s mother was pregnant with their last child, and she wanted to give birth in the country that she considered her homeland. By December, Léon Bivas believed that the situation was safe because the new President, Mohamed Naguib, was known to be friendly to Jews. So the family returned to the spiderweb building. But post-revolution Presidencies have a way of ending abruptly, and, after less than a year, Naguib was unseated by Nasser. Nasser’s feelings about Jews had been hardened by his military experience in the Arab-Israeli War of 1947, when the Israelis had routed the Egyptian forces. In 1956, the year that Nasser won the Presidential election with more than ninety-nine per cent of the popular vote, the Bivas family went to France again. This time, they packed as much as they could in their luggage.

Léon Bivas returned to Cairo alone, to deal with the factory. In July, Nasser seized the Suez Canal, and the resulting war, in which Israel fought alongside the British and the French, represented the end for Egyptian Jews. Nasser’s government arrested hundreds on the suspicion of espionage and other crimes, and a new exodus began. In the span of three months, at least ten thousand Jews fled the country. A number of former Nazi officials had sought refuge in Egypt after the Second World War, and some of these men reportedly helped Nasser’s government design anti-Semitic laws. Egyptian nationality could be revoked from anybody who was declared to be a “Zionist,” a term that was never defined. Soon, Jewish Egyptians were limited to a single piece of luggage on departure. Anybody carrying significant funds out of the country could be arrested.

By this time, Albert’s grandparents were elderly, and they were allowed to leave on one-way passports—the documents specified that they were good for only a single journey. They left in such a hurry that they didn’t sell the spiderweb building. In France, the passports of Albert, his mother, and his four sisters expired, and the Egyptian Embassy refused to renew them. France classified the family as stateless. In less than a year, they had gone from prosperous residents of a family-owned building to refugees.

In Cairo, Léon Bivas was trapped in the ground-floor apartment. The government refused to grant him travel documents, and he was placed under house arrest. Outside the webbed gates a guard was stationed, and he escorted Bivas to the textile factory every morning. Bivas ran the factory as a virtual prisoner for more than a year. It was nearly impossible for an Egyptian Jew to sell a significant asset, because buyers knew they could just wait for things to get worse. Finally, the factory’s Egyptian foreman bought the business at a steep discount, which presented Bivas with a new problem. He couldn’t carry or transfer cash out of Egypt. But he had an idea. He bought two pairs of roller skates and mailed them to the twins.

Leave a Reply