There is more to Sephardi culture than cuisine and music: their vast intellectual contribution to Judaism is slowly being recognised. Article in Hasepharadi by Henry Aharon Wudl:

Before the demise of the Jewish communities of the Middle East and Mediterranean regions in the middle of the twentieth century, their migration away from their countries of origin, and their resettlement in the West and Israel, the Sephardic ḥakhamim and intellectuals produced an immense literature that spanned the whole range of traditional Jewish learning: Biblical exegesis, Talmudic commentary, halakhic treatises and responsa, musar (ethics), philosophy, Kabbala, grammar and poetry.

It is known that this literature’s history extends back to the early Middle Ages, to the era known as the ‘Golden Age of Spain’ (more specifically Al-Andalus), when the Muslim Middle East was the world center of dynamic intellectual creativity, in which the Jews were engaged as much as their Muslim and Christian neighbors, and out of which came such luminaries as Maimonides, Seʿadia Ga’on, R. Yehuda HaLevi, and Bahya ibn Pakuda, whose works have become Jewish classics and are well-known and studied to this day.

What is less well-known is that, while the ‘Golden Age’ may have gone into decline, intellectual creativity never ceased in the Sephardic world, and continued down to modern times- contrary to the perception of Sepharadim which prevails in today’s Ashkenazi-dominated Jewish world, according to which Sepharadim are, almost by definition, conservative, tradition-bound, patriarchal, and entirely lacking a coherent response to the challenges of modernity; the latter, it is assumed, they never experienced prior to their emigration to North America, Europe or Israel.

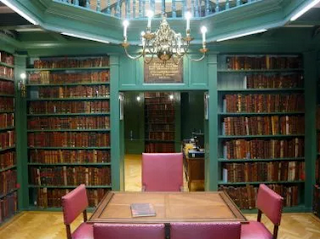

The ancient Etz Hayim library, founded in 1639 by Portuguese Jews in Amsterdam (Photo: Jessica Spengler)

R. Moshe HaKohen Khalfon’s powerful writings on charity, social justice, and world peace (written in the wake of World War I), firmly and yet creatively grounded in Jewish thought, are almost inaccessible to most. Jewish thought that engages creatively and insightfully with modernity, we are given to understand, has been the exclusive preserve of Ashkenazi intellectuals.

Most Jews today who have received a decent Jewish education know of figures such as R. Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, R. Samson Raphael Hirsch, Martin Buber, Franz Rosenzweig etc. But very few have heard of R. Yiḥya Qafiḥ of San’a, who strove to revitalize his community by promoting the classical rationalist Jewish thought of Maimonides and Saʿadia Ga’on, writing sustained and intense polemics against Kabbalah, and opening a school which taught science, mathematics, Arabic, and Turkish alongside Bible and Talmud.

Not many know of Shadal (Shemuʿel David Luzzato), the head of the Rabbinical College of Padua, who promoted academic methodology for the study of classical texts in the seminary and opposed both Kabbalah and rationalist philosophy of the Maimonidean sort – or of Umberto Cassuto, a product of a similar rabbinical college in Florence, who saw no contradiction between being a strictly observant rabbi and a critical Bible scholar. Few have seen the responsa of Moroccan rabbis like R. Yoseph Messas and their fearlessness in attempting to synthesize halakhic solutions to some of modernity’s most pressing challenges, their permitting the use of electricity on Yom Ṭov, their inclusive approach to converts (including those who convert for the sake of intermarriage) and their encouragement of women who wished to study Talmud.

The Tunisian R. Moshe HaKohen Khalfon’s powerful writings on charity, social justice, and world peace (written in the wake of World War I), firmly and yet creatively grounded in Jewish thought, are almost inaccessible to most.

Leave a Reply