Forty years have passed since the signing of the Israel-Egypt Peace Treaty but the Egyptian government has made no progress in meeting the property claims of Egyptian Jews. Lyn Julius explains the situation, in this extract from her book Uprooted: How 3000 years of Jewish civilisation in the Arab World Vanished Overnight.

The 1979 Camp David Treaty declared: ‘Egypt and Israel will work with each other and with other interested parties to establish agreed procedures for a prompt implementation of the resolution of the refugee problem’, without specifying if the refugees were Jewish or Arab. Under Article VIII of the Treaty, the two sides agreed to establish a Claims Commission for the mutual return of financial claims. But the Claims Commission was never established.

In 1980, an Egyptian Jew, Shlomo Kohen-Tsidon, wrote to Menahem Begin suggesting that, in the absence of a Claims Commission, the state of Israel was now responsible for meeting Egyptian-Jewish compensation claims. But Kohen-Tsidon’s interpretation was rejected by Israel’s foreign ministry.

Why was the Claims Commission never established? Egypt has never pressed for it. The Egyptians initially realised that Israeli claims could leave Egypt ‘stripped bare’, as one Israeli source put it. Israel, for its part, feared that Egypt might file a massive claim for oil pumped from the Abu Rudeis fields in western Sinai between 1967 and 1975. In anticipation, Egyptian Jews formally asked the Israeli government in 1975 not to return the oilfields without claiming compensation for Jewish property claims. Israel did not do so, and the Organization of Jews from Egypt sued the state of Israel before the High Court of Justice in September 1975. They lost the case, however: the Attorney-General Gabriel Bach concluded that it was too late. The agreement returning Abu Rudeis to Egypt had just been signed.

Levana Zamir, then head of the Israel-Egypt Friendship Association, argued that the UN Charter on Wars between countries stipulates that no natural resources need be returned in peacetime. Therefore, the oil pumped by Israel from Abu Rudeis should not have been taken into account.

The government of Israel produced a variety of excuses for not pursuing Egyptian-Jewish claims. In the end they claimed that, at the time their property was taken from the Jewish refugees, they were not Israeli citizens. As one Egyptian Jew ruefully remarked, this argument never stopped Israel from claiming from Germany on behalf of Holocaust victims.

The late Israeli minister of Justice, Yosef ‘Tommy’ Lapid, declared in 2003 that the failure to resolve Egyptian-Jewish claims was a severe omission by Israel – and its reticence on the question of Jewish refugees ‘one of the greatest blunders in the state’s history’.Meanwhile, Justice for Jews from Arab Countries has given a renewed impetus to the collection of claims, although they now declare recognition of refugee rights, not redress, is their top priority. (…)

The Cecil Hotel is the only known example of property restituted to its Jewish owners. In 1956, the Jewish owners of Cecil Hotel in Alexandria were expelled from Egypt. They left with one suitcase. Nationalised five years before the family was expelled, the eighty-six-room hotel was resold to Egypt after its return.39 In its heyday the Cecil hosted such figures as Winston Churchill and Al Capone. In 1996, an Egyptian court ruled that the hotel should be returned to its owners, but the ruling wasn’t implemented for fear it would establish a precedent for the restitution of nationalised Jewish property.

After a fifty-year struggle, the Egyptian government agreed to compensate the Metzgers. The hotel’s owner, Albert Metzger, died in Tanzania in the 1960s and his son Chris continued the struggle to recover the hotel. In 1996, the Egyptian Supreme Court in Cairo ruled that the hotel and all revenues accruing over the years belong to the Metzgers. But only in June 2007 did the Egyptian government propose a deal whereby the government would agree to implement the court ruling but would immediately buy back the hotel from the Metzgers.

Now living in Canada, the Bigio familyhave been engaged in a long- running battle for justice against the giant multinational corporation Coca- Cola. The Bigios are among the many Egyptian Jews from whom the Egyptian authorities under Nasser’s ‘Arab socialist’ regime expropriated and nationalised land and property. In November 1961, the Beirut newspaper al- Hayat printed the text of a Nasser decree, which stated that ‘all Jews included in the list of sequestrations are deprived of their civic rights and cannot serve as guardians, caretakers or proxies in any business association or club’.

After Nasser’s regime expropriated the Bigios’ Heliopolis plants, producing Coca-Cola under licence and bottle caps, the family fled Egypt and the UN classified them as refugees. They made their way to France, where they were granted asylum. Determined to obtain compensation for the family’s assets, the Bigios undertook several trips to Egypt. In 1979, the Egyptian government finally issued an official decree returning their real estate assets. But when the time came to receive these

The Bigio family, fighting for restitution of their bottling plant in Egypt (Wikimedia Commons)

assets, a state-owned insurance company, which was holding the property, refused

to return them. The Bigios took their legal fight to the US when they learnt that their assets had been acquired by Coca-Cola International. In 2011, in the US federal court, the Bigio family lost their case for justice against the Coca-Cola Company: the latter had managed to avoid presenting detailed factual evidence of their direct involvement in the acquisition of the Bigio family’s real estate assets and factories. Instead, the US court, upholding (together with the Egyptian government) the family’s right to compensation, pointed to the liability of a subsidiary of Coca-Cola.

For its part, Egypt has reacted with paranoia to Jewish property claims. Media hysteria caused a roots trip fromIsrael to be cancelled in 2008 on the grounds that elderly Egyptian-born Jewish tourists were coming back to reclaim their property. From time to time, the press scaremongers about ‘Jewish documents’44 which it alleges Jews are attempting to steal and smuggle out of the country to support their claims for property restitution. But the vultures – unscrupulous lawyers and property developers – are circling: the Jewish community has untold assets in real estate. Its synagogues may be crumbling but they stand on prime property in Cairo and Alexandria. The sprawling Bassatine cemetery, where community leader Carmen Weinstein was buried and which she fought to salvage from squatters and vandals, used to be on the outskirts of Cairo; now it occupies precious acreage virtually in the centre. Then there are the thousands of homes and businesses seized from or abandoned by Egypt’s 80,000 Jews in their mass exodus. Egypt’s worst nightmare is that the Jews should return and claim it all back. In the meantime, property deeds are being forged and false ownership claims made.

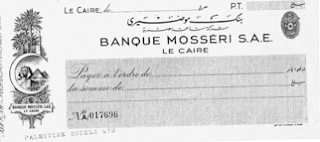

In an ironic reversal of roles, an Egyptian bank is even suing the Israeli government for the return of shares in the King David Hotel, Jerusalem.

Cheque from the Palestine Hotels Ltd account with Banque Mosseri. Egyptian Jews held shares in hotels such as the King David in Jerusalem.

The Jewish-run Bank Zilkha, which held 1,000 shares in the hotel, was taken over by the huge Egyptian Banque Misr. Clearly, the sums owed to Banque Misr would be dwarfed if the Israeli Administrator General were to sue for the billions owed to Jewish refugees from Egypt.

Leave a Reply