In the early years of the state around one in eight Yemenite babies, many of them sick, disappeared and it is alleged that some were ‘sold’ to US families for adoption by WIZO, the US Women’s Zionist Organisation, a new TV documentary alleges. There was a three-month window to allow parents to reclaim their children, however and this article does testify to the mayhem prevailing at the time, in which no adequate records were kept. Neglect, yes – but was there a state-sponsored conspiracy? No outright proof exists. (With thanks: Lily)

Last December, the Israel State Archives released more than 200,000 previously classified documents pertaining to this decades-long affair that has come to symbolize the grievances of Mizrahim (Jews of Middle Eastern or North African origin) against the establishment. They include testimonies of parents who searched in vain for their missing children and their graves for decades; of hospital nurses who witnessed children being given away without permission; and of children sent off for adoption who later tried to reconnect with their biological parents. However, the documents provided no outright proof of an organized and institutionalized abduction campaign.

The newly declassified papers also include minutes from the hearings of the commission of inquiry established in 1995. Like the two previous commissions that investigated the affair (the most recent being by Justice Moshe Shalgi in 1988), this one also found that most of the Yemenite children who disappeared had died of illness. While the fate of several dozen children is still unknown, the most recent commission of inquiry determined that none of the children had been kidnapped.

The new documentary challenges these findings. A key testimony is provided by Ami Hovav, who worked as an investigator on two of the three commissions of inquiry. In an interview with Rina Matzliach, the Channel 2 correspondent who made the film, Hovav addresses the role of machers, or middlemen, in the disappearance of several children. As part of his duties on the commissions, Hovav had been asked to investigate reports, published as early as 1967, that Yemenite children had been abducted and sold to wealthy Jews abroad for $5,000 a head.

Interviewed in the film, Hovav relays that many of the Yemenite babies and toddlers were put in child-care centers run by the Women’s International Zionist Organization (WIZO), one of the largest Jewish women’s organizations in the world.

“There was a rule at the time that if the parents didn’t show up within three months to reclaim their children, the kids would be sent off for adoption,” he states. “So there were these machers who would come and get $5,000 for each child that was adopted.”

But it would be wrong, he says, to describe such transactions as sales: “This was a commission they took, just like real estate agents. This was their job.”

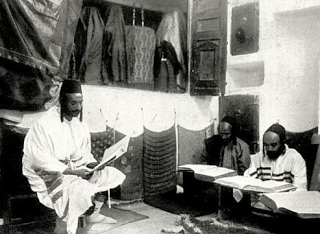

Rare photos of Yemenite Jews in Sana’a taken by the German-Jewish adventurer Herman Burchardt in 1901. Full article in Haaretz here.

The film provides never-before-seen footage, shot by (the late campaigner Uzi) Meshulam’s followers, of the 1995 commission of inquiry hearings. At one point, Sonia Milstein, the head nurse at the Kibbutz Ein Shemer absorption center, recounts how Yemenite children were systematically separated from their parents and put in childcare centers. When asked to explain why no records of their whereabouts were ever kept, she responds: “That was the reality then. It was what it was.”

In more rare footage, a former doctor at a WIZO center in Safed tells her interrogators at the commission hearings she has no recollection of what happened to the Yemenite children housed at her facility. Commenting in the documentary, Drora Nachmani – the lawyer who interrogated the doctor and other witnesses – notes that this sudden loss of memory among WIZO staff members was not uncommon.

“Some of the WIZO witnesses didn’t want to come to the hearings, and we would have to chase after them,” she tells Matzliach. “Often, they would insist we come to them rather than they come to us, as if they were afraid of something. And sometimes they said one thing to one investigator and something else to another.”

According to Nachmani, the WIZO day-care centers “were often the last stop or the second-last stop in the whole chronology of events” surrounding the disappearance of the Yemenite children.

“They were a central junction in this whole story,” she states.

The documents recently declassified by the Israel State Archives were meant to stay under wraps for another 15 years. But in response to public pressure, the government decided to release them sooner.

Mizrahi activists had been urging the government to open the state archives for several years, arguing that the various commissions of inquiry whitewashed the affair. A driving force behind the campaign has been an organization called Amram.

Interviewed in the film, founding member Shlomi Hatuka notes that out of more than 5,800 Yemenite babies and toddlers known to have been alive during the first years of the state, 700 disappeared. “That is one out of eight children,” he tells Matzliach. “And if you take into account those parents who didn’t report their missing children, it’s probably closer to one out of seven, or one out of six.”

The irony, he notes, is that families were told their children were being moved from absorption centers to child-care centers for reasons of health and sanitation, but many became ill there, ending up in hospitals from which they never returned.

To illustrate the atmosphere of mayhem in those early days of the state, Hovav recounts a story he heard from Milstein, the head nurse, about what would happen when sick babies were taken to the hospital. “An ambulance driver would pick them up and the babies would be put in cardboard boxes that had been used to transport fruit, bananas or apples,” he relays. “And there would be five or six of these boxes in the back.”

Each carton, according to his account, had a little note attached to it bearing the child’s name, address and destination. “When it would get very hot,” he recounts, “the ambulance driver would open the window and a huge blast of wind would come in. What would happen then is that all those little notes would start flying in the air. They would stop the ambulance on the side of the road, but they had no idea after that which note belonged where.”

Asked to comment on the allegations raised against WIZO in the film, a spokeswoman issued the following statement: “The process by which children were admitted or left our facilities was handled exclusively by the certified state authorities, while WIZO’s role was restricted to caring for their health and welfare. The allegation that the organization played a central role in transferring the children to adoptive families is erroneous and is merely someone’s personal interpretation of events. The same is true about allegations raised by some of the interviewees in Rina Matzliach’s film.”

Leave a Reply