This year is the 180th anniversary of the mass forced conversion of the Jews of Mashad to Islam. Largely thanks to their women, who remained isolated from social and religious pressures, the Jews proceeded to lead a double life – Muslim outwardly, but Jewish at home – which helped preserve their identity at the height of adversity. Dr Mehran Levy summarises their story in Kinloss magazine (with thanks: Michelle)

The extraordinary history of the Jews of Mashad began during the reign of Nader Shah (known as the ‘Napoleon’ of Persia) of the Afshar Dynasty, who ruled from 1736, and his empire briefly stretched across present-day Iran, India, and parts of central Asia.

At the time, for over 2500 years, Jews lived in various provinces of Persia. They were engaged in trade but were also bankers, and ran depositories. The Shah brought forty Jewish families – trustworthy and reputed for being good financiers and honest business people – to his capital Mashad to run his business, while seventeen families were sent to the nearby city of Kalat, his seat of residence.

Jews were appointed to manage the Shah’s vast treasures (including the largest diamonds – Kohinoor and Dariyanoor) brought in after the conquest of India. Initially, they resided in a shanty precinct called Eidgah (Ghetto). Meanwhile, the Zoroastrian community of Mashad, subjected to religious annihilation, were fast evacuating the area. This gave the opportunity to the Jews to purchase their lands and properties, and the Shah sanctioned them to build synagogues and community centres.

Nader Shah, the community’s only hope and saviour, was assassinated shortly afterwards in a rebellion (1747). The country was fragmented and revolts erupted between his successors. Several families tried to flee eastward, to Herat, Bukhara and on to India. In spite of the long and dismal period that followed, the rest of the community remained united, alert, vigilant. It designated elders to solve disputes and to liaise between the Jewish and the Muslim population. The whole of Eidgah was interlinked with small inconspicuous doors, which could be used as escape routes at times of trouble. The windows faced alleyways rather than areas where onlookers could see into the private dwellings.

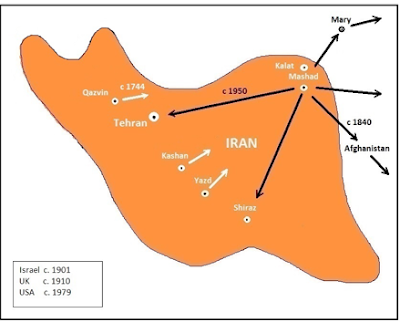

Migratory routes taken by Mashadi Jews

The Jews established business links with local Muslims as means of survival including trading woollen clothes, silk, and other textiles.

There were many assaults on Mashadi Jewry, the most poignant in 1839. The 180th anniversary of falls this year and the community is commemorating and reflecting upon it. An incident occurred when the inadvertent misconduct of a Jew resulted in the killing of several Jews by a mob. This was the catalyst for more persecution, giving rise to one of the darkest epochs in the lives of Persian Jewry, followed by the forced ‘conversion’ of Jews to Islam. Within days, the entire community of about 400 families was forcibly converted to Shia Islam, some were killed and most community centres, including synagogues, destroyed.

These Anusim (forced converts) among the Mashadi Jews were known as Allah-dadi (God given)and recognized as Jadid al-Islam (New Muslims). The sceptics, to ensure they no longer practised their ‘idolatrous’ religion kept the ‘New Muslims’ under surveillance. The ghetto was renamed Mahalleh Jadid (The New Precinct). This grim situation motivated a large number to leave for the Land of Israel and the nearby cities in Persia where they assimilated into the existing Jewish communities, or moved to more tolerant Afghanistan and Turkmenistan.

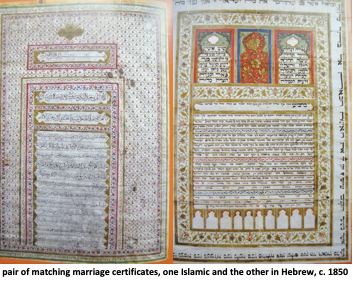

However, those who remained continued to adhere tenaciously, although undercover, to their orthodox religious activities and began to live a dual life. Kashrut, marriage, and burials were all conducted under strict Jewish laws. Intermarriage was unknown within the community – girls were betrothed to Jewish boys at an early age to avoid a forced marriage to outsiders. The marriage ceremony would be first conducted in a local mosque by the Imam, and then carried out under rabbinic auspices; having two marriage certificates, one in Persian and one in Hebrew, was common. Men had dual names, a Persian Arabic name as well as their Hebrew birth names.

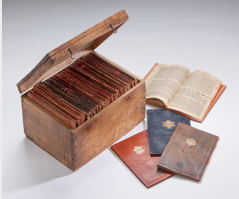

Men attended mosques for daily prayer followed by davening in their secluded synagogues. To make them inconspicuous, miniature Tefillins, Siddurim, and Torah Parshiots printed as separate smaller booklets (read in services even to this day) were in use. A unique form of scriptwriting known as Jadidi (new) was created – this was a mixture of Persian and Hebrew only understandable by the Jews at the time. Some even went on to Mecca for pilgrimage and were commonly ennobled by the title Hajji after returning from Hajj.

Mini-parashiot booklets printed in Lithuania in 1900 and used in Mashad c. 1918 (Photo: UMICA)

Because of this duality, there were no openly Jewish schools in Mashad. Pupils attended local primary and secondary schools while the elders, behind closed doors, taught Jewish studies. When the Alliance Israelite offered education classes, the elders, fearful that their secret faith may be exposed, rejected it. This inevitable but wise decision had damaging ramifications for the community because they were comparatively less educated than their Jewish counterparts in Iran in the first half of the twentieth century.

Mashadi Jews have been unique in the diaspora because for centuries, they maintained their Jewish faith and practised Orthodox Judaism to the full, if underground, in an Islamic environment. Historians argue that this was due largely to the women who were somewhat excluded and segregated from the public domain and the city’s fervently religious atmosphere. The characteristics of the traditional Iranian home and the segregated closed unit of the Jewish household meant that the women had, comparatively, a greater degree of liberty to live as Jews in their homes. Hence, they upheld their ancestral traditions and passed on that unadulterated faith to the next generation.

Young Mashadis never witnessed or experienced the lives of their parents in Iran. However, in their unique and highly integrated social life outside Iran, and the negligible rate of intermarriage, they have upheld their traditions. They are well-educated, informed and are involved in wider academic, corporate and political institutions.

From the outset, the crypto-Jews of Mashad, consciously or not, believed that it was best not to assimilate and to remain unnoticed and united within their tightly-knit community. Some attribute this to the community’s double life in the past as a means of survival and believe that their parents’ socio-cultural lifestyle has perpetuated itself and is apparent in the present day. However, it is certain that this unique lifestyle has worked in their favour, keeping the community integral, safe, prosperous and, remarkably, preserving their orthodox Jewish identity unhindered for centuries in the face of extreme adversity.This trait is unlikely to erode in the near future and perhaps unwittingly, they have formed their own diaspora within a diaspora.

This article, written in memory of the author’s father, has been reproduced with the kind permission of Dr Mehran Levy.

More about the Jews of Mashad

Leave a Reply