For the great mass of Jews fleeing Arab countries, adapting to their new countries meant cultural adjustments, as Lyn Julius describes in her new book Uprooted.

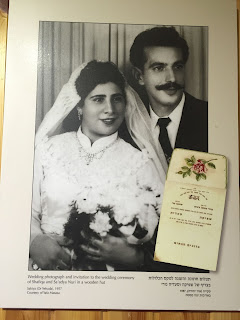

Invitation to the wedding of Shafika and Saadiya Nuri in a wooden hut (Photo by permission of Or Yehuda)

One word encapsulates the Mizrahi refugee experience in the Israel of the 1950s and 1960s: ma’abara. Ma’abarot were transit camps of fabric tents, wooden or tin huts. They were conceived by Levi Eshkol of the Jewish Agency to provide temporary housing and jobs. The first ma’abara was es- tablished in May 1950 in Kesalon in Judea.

The EU as a whole, with a population of over 300 million, has been taking in as many immigrants as Israel, a country of half a million, absorbed in the early 1950s. As well as 100, 000 Holocaust survivors, the tiny struggling country took in 585,000 Jewish refugees from Arab countries, most of them destitute. By the 1960s, the refugees had tripled the country ‘s population. The size of Israel’s endeavour was Herculean. A nation of 650,000 absorbed 685,000 newcomers, some arriving with dysentery, malnutrition, ringworm, trachoma and TB.

During the first years of statehood, roughly two-thirds of Jews from Muslim countries availed themselves of the Law of Return, passed by the Israeli Knesset in 1951. The newcomers came to Israel on some of the largest airlifts in history. It was a miracle that there were no accidents. The chartered aircraft were overloaded and fuel was short. Desert sand damaged the engines. It took sixteen hours for Yemenite Jews to reach Israel, and planes from Iraq were, at first, not permitted to fly direct.

Conditions in the ma’abarot were deplorable – too hot in summer, too cold in winter, exposed to the wind and the rain. Everything from food to detergent was rationed.

Refugees had to line up to collect water from standpipes. The water had to be boiled before it could be drunk. The public showers and toilets were rudimentary. The 113 ma’abarot housed a quarter of a million people in 1950.

Slowly the ma’abarot turned into permanent towns. Some residents stayed in the camps for up to thirteen years. ‘Bring a million Jews’, declared Ben-Gurion. But news of what awaited them deterred those Jews still in Arab countries from joining their relatives in Israel. Bitter and disappointed Iraqi Jews spread rumours that the Mossad had planted bombs in order to make them leave the ‘paradise’ that was Iraq. Later, there arrived in Israel Moroccan Jews, disparaged as ‘Morocco sakin’ (cut-throats), who, faced with multiple hardships, idealised the sultan of Morocco as their protector and saviour.

The male heads of household in particular never got over the degradation of becoming refugees. Raphael Luzon writes of his father, who once owned several pharmacy and cosmetics stores in Benghazi, Libya, until the family were forced to leave in 1967:

After his soul surrendered, his body followed and soon he became ill with kidney failure. Apart from a brief stint in employment, he refused to work. Once a man of wealth, he never would have thought about standing in line at the soup kitchen with charity coupons to get meals for himself and his family. My mother urged him to fight back, but her words fell on deaf ears. He had long ago lost the will to live.

Other newcomers remained quietly philosophical: Egyptian Jews incongruously maintained their bourgeois cultural habits in the camps – playing cards and ballroom dancing on a Friday evening.

The Jewish state wished to build a new national identity and fashion those Jews who did reach its shores in its own Western image. Many refugees launched themselves with gusto into the task of nation-building, making an effort to speak only Hebrew (Arabic was often associated with unhappy memories) and even Hebraising their family names. The young people were carted off to kibbutzim to learn Hebrew and controversially secular Western values, wear shorts and mix socially with the opposite sex for the first time, as Eli Amir describes in Scapegoat.

But these values were actually ‘only slightly Western’, as Yitzhak Bar Moshe discovered when he arrived from Iraq. Israel was the state of Eastern European Jewry. With the exception of rare figures like President Yitzhak Ben Zvi, it did not know about Mizrahi Jewry – worse still, it did not want to know about them, their sages, their rabbis, authors, paytanim (poets) or judges: ‘We understood that we were one of many communities. We left Iraq as Jews and we entered Israel as Iraqis.’

Still, cultural adjustments were necessary in all facets of life. Shmuel Moreh’s father could not comprehend the lack of corruption in Israel:

He used to say, gritting his teeth: ‘By God, I don’t understand this up-side-down country. May the Lord have mercy on Iraq. There we knew how to calculate our steps. Open your hand a bit, slip a few dinars into the official’s hand in order to grease the process of your request a bit and everything will fall right into place. Here there is no bribery, there is no cronyism and there isn’t the magical religious saying: ‘Do it for the sake of God! Do it for the sake of the Prophet Muhammad!’ Here everything is according to the dark law of the inhabitants, a law I don’t understand’.

For the family of Chochana Boukhobsa, who came to Paris from the small Tunisian town of Sfax, cultural differences had some hilarious side-effects. Her grandfather, a ritual slaughterer, had brought with him his sharp knives and the habits of a lifetime. Her mother paid top price for a cockerel she found on the Seine quayside.

The cockerel stayed under the kitchen sink of our tiny apartment on the rue de la Roquette. He crowed at the crack of dawn. Puzzled neighbours searched the whole block looking for him. ‘Did you hear a cockerel crow?’ They asked my mother. ‘No’, she answered, mortified. As soon as the door shut, she told my grandfather. ‘Quick, kill that cockerel and be done with. In this city, the police come after those who keep live birds in their apartments.’

From ‘Mizrahi Wars of Politics and Culture’, in Uprooted: How 3,000 Years of Jewish Civilisation in the Arab World Vanished Overnight by Lyn Julius (Vallentine Mitchell). Available on Amazon.

Leave a Reply