Important article in the Tel Aviv Review of Books by Shmuel Trigano pointing to the essential Islamic context behind the violent suppression by Ottoman sultans of the nascent nationalism of three dhimmi peoples – Greeks, Armenians and Jews – in the 19th and 20th centuries. Professor Trigan”s book ‘Juifs en terre d’Islam’ was recently published in Hebrew.

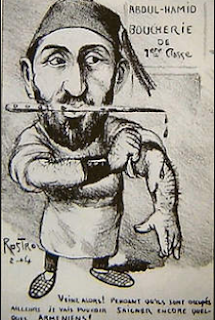

Caricature of Sultan Abdul Hamid as a ‘first class’ butcher following the Ottoman massacres of Armenians in the late 19th century

Succumbing to the pressure of the European Christian powers, the Ottoman Empire was forced to change the status of dhimmis . The Tanzimat reforms of 1839, enacted by Sultan Abdul Mejid, followed by the edict of Hatt-I humayun of 1856, enshrined the principle of equality for all subjects of the empire irrespective of their religion. However, it preserved the structure of communities or “nations” , by changing their administrative function and keeping the hierarchy intact (with the Greeks, Armenians and Jews at the very bottom).

If these reforms had in effect undermined the established order of the communities and emancipated their members, it was a traumatic insult for the Muslims whose millet had lost its privileged status, making it one nation among many— an insult compounded by the fact that the reforms were imposed by Christian powers. For the Muslims, this evolution was nothing short of the complete capitulation of Islam and the abandonment of its legitimacy. Yaron Harel has shown that in Syria and Lebanon, the Tanzimat reforms changed nothing regarding the segregation of the communities across all areas of everyday life.

In fact, before the Tanzimat the longing for independence among the dhimmi peoples had already begun with Greece’s 1822 War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire. Greece’s victory showed that Independence seemed within reach. Though generally forgotten, Zionism began in the Turkish Balkans in Sarajevo with Yehuda Alkalai and not in Europe with Herzl. Inspired by the Greeks, Alkalai developed an extensive theory of Jewish sovereignty and travelled throughout Europe and the Middle East to spread his ideas. Herzl heard of him in Vienna.

After the Greeks and the Jews it was the turn of the Armenians. The national awakening of these three dhimmi people led to the Arab nationalist movement and also the first Islamic repression. The Armenians, under the impetus of the movement of nationalities, committed an act of rebellion against the dhimmi by fighting for national autonomy. After several rebellions in the Caucasus, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation was established in 1890 in Tiflis, and advocated an armed struggle for liberty.

In 1893, Armenian nationalists made public appeals across Armenian territories to rise up against the Sultan’s oppression. A violent response ensued: several massacres were carried out by the Ottomans in 1894-5, in Sason, Constantinople, Trebizond and other places. The death toll stood at somewhere between 100,000 and 300,000 people. Often overlooked is the Jihadi nature of these massacres: not only in their motivation and their legitimation, but also in the nature of the acts themselves and the fact that the surviving women and children (some 150,000) were forcibly converted to Islam. The same pattern was to reappear in the second wave of genocide, this time instigated by the Young Turks, who had toppled Sultan Abdul Hamid in 1908.

The transition from a caliphal regime founded on religion to a Turkish state centered on the nation, doing away with the Ottoman system of power, cultivated hopes of liberty among the nations of the empire. But this was not to be the case; here too, the Armenian case comes in handy in highlighting the prevalent role played by Islam in modern nationalism in the Turkey—a Muslim, albeit not an Arab, state.

The peaks of Armenian oppression came about against markedly different backdrops but were eventually similar in essence. The massacres of the late nineteenth century were the doing of an imperial power bent on suppressing any attempt to question its authority, religious in effect, which applied to the entire Ummah and derived its power from the and the religious sentiments of its subjects.

Hit with the reforms, the massacres provided an outlet for their resentment. For the Young Turks, it was the Turkish nation and its ethnicity—their Turkishness—in the spirit of the nationalist movements that consecrated the ethnic homogeneity of the emergent nations, then transformed into a “rationally” thought out and systematically implemented political plan.

In this respect, the Armenian massacre of 1915-1916, with its 1.2 million victims, paved the way for the genocides of the twentieth century. This plan was later fully achieved via population swaps between Greece and Turkey (1,750,000 displaced persons on both sides). Between 1923 and 1930, 1,250,000 Greek Christians were banished from Turkey, while a smaller number of Turks left Greece for the motherland.

Leave a Reply