Egypt is less well known for its interwar Jewish writers than Iraq, for instance. Nevertheless, according to HaSepharadi, poets did exist, writing primarily in French. They extolled the ‘tolerant’ Pharaonic past and their sense of belonging to Egypt. (With thanks: Boruch)

One notable case, however, is the Cairo Jewish writer Ya’qub Sannu’, who is predominantly remembered for his significant role in late nineteenth-century Arabic journalism and theater. Respectively, virtually all the texts written in Egypt in Hebrew, during colonial and monarchic times, were rabbinical studies. The choice of writing in French thus depended on one’s education and family background, but was also due to the fascination that France, and especially Paris – as a global capital of culture – held for the Egyptian middle class.

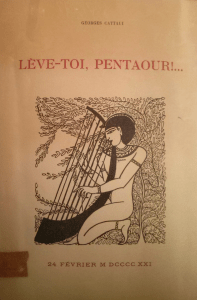

“Wake up, Pentaour, and sing a novel song! A song of grace, of euphoria, a song of joy!”: these words open Georges Cattaui’s 1921 poem Lève-toi, Pentaour! Cattaui was born in Paris in 1896, a son of one of the most prominent families of the Cairo Jewish elite. He was educated in both France and Egypt, and in the 1920s after acting as secretary to King Fuʾād, began work as a diplomat in Prague, Bucharest, and London. In the 1930s, he embarked on a full-time literary career. He converted to Catholicism in the 1920s and subsequently left Egypt for France and Switzerland, where he died in 1974.

In Lève-toi, Pentaour!, Cattaui goes back to the Pharaonic era, using it as a lens to discuss early twentieth-century Egypt. The protagonist is Pentaour, priest, poet, and scribe of Ramses II, who wrote a poem about the Battle of Kadesh (1274 BC), where the forces of Ramses II battled the Hittite empire. From the distance of a millennia, Cattaui celebrates the upcoming Egyptian independence from the British, which would lead to the birth of the monarchy in 1922:

Egypt, among perishable people,

you kept your essential character for four thousand years,

you are here again without a yoke, without a chain under your sky,

you are here free again ruling over your sand!

On the tomb of Amrou, may, oh Muslim,

this holy day be blessed among your propitious days!

[…]

Blessed be this day, oh Jew, next to the Nile whose waters

took the fragile cradle of Moses;

and you, oh Copt, in your mysterious church,

where the Virgin and the Child rested!6

Cattaui evokes a nation where Muslims, Jews, and Copts live together peacefully and stresses how Egypt maintained its unique characteristics against all odds for four thousand years. His words echo ideas of Egyptian exceptionalism, which in the 1920s expressed itself through Pharaonism, vis-à-vis the other Middle Eastern countries. According to Cattaui, Egypt had a separate identity, rooted in the country’s ancient past, which went beyond its Islamic heritage and made it different from the rest of the Arab world.

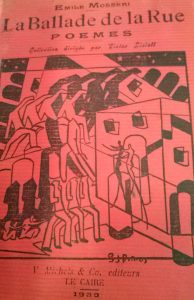

Cattaui was not alone in attempting to inscribe the Jews within the Egyptian national narrative. A second notable author is Emile Mosseri, born in 1911 into another upper-class Jewish family in Cairo. A lawyer by training, Mosseri wrote several plays and collaborated with magazines like L’Egyptienne. Mosseri’s most important achievement was the publication of the collection of poems La ballade de la rue in 1930.

The poem J’ai marché quelque soir describes a visit of the poet to Luxor:

I marched one night when the moon was round,

in the temple of the gods of Thebes and Luxor

[…].

I passed under your shadow at this hour when everything sleeps,

and I thought that just like the priest of Hathor

a people followed me, enlivening the blonde night.8

Mosseri travels back to ancient Egypt in search of his lost past and identity, wandering around the ruins of the city. The evocation of ancient Egypt and its archaeological vestiges had a clear national connotation and reinforced claims to Egyptian sovereignty. Let us also recall the Arab Egyptian poet Ahmed Shawqi, who talked about Pharaonic ruins as markers of the country’s national past. In the case of the Jews, ancient Egypt related to one of the most important episodes of the Tora, the Yeṣiʾath-Miṣrayim (“Exodus from Egypt”). This ancestral connection to the land was of utmost importance in the 1930s, when notions of citizenship and the status of minorities were being discussed and the Egyptian liberal party system entered into a crisis.

Egyptian Jewry, around the 1930s, exhibited strong sentiments towards Egypt, celebrating its modernity and their ability to maintain their religious and national feelings of belonging. This received particular importance, as Europe was becoming an inhospitable environment for Jews. Subsequently, some found solace in the promises of the past, among Muslim countries:

…the green banner [of Islam],

on a tent or on a city,

declares to the man who follows a desert road:

‘Come, brother, the door of hospitality

is wide open!’.

[…]

It says: ‘Oh brothers of race,

let us ask together, kneeling,

that God keep us under his grace,

that he protect us and encourage us,

and that peace may be upon us!’

The author of these lines is Lucien Sciuto, a journalist of Jewish origin born in Thessalonika, Greece, in 1868 who later moved to Cairo in 1924 and died in Alexandria in 1947. The poem Islam is taken from his 1938 volume Le peuple du messie. The book, written “under the Egyptian sky, on the borders of the desert, in a serene and peaceful setting,”was dedicated to Faruq, the second and last King of Egypt, who reigned from 1936 to Nasser’s Revolution in 1952. Sciuto, in his poem, wrestles with the fact that at the time he was writing, Europe had become an inhospitable place for Jews; yet in the Islamic world, they had found and could still find refuge from persecution.

Leave a Reply