Following yesterday’s post revealing Mossad involvement in Algeria, this is a detailed account by Jessica Hammerman of a little-known episode in the Algerian war for independence from France in May 1956: a two-day battle between Jews and Muslims in the city of Constantine. Encouraged by undercover Mossad agents, armed Jews ‘defended themselves’ against terrorism in the absence of the French police. But much to the agents’ embarrassment, self-defence seemed to degenerate into a lethal anti-Muslim riot. (By kind permission of the author).

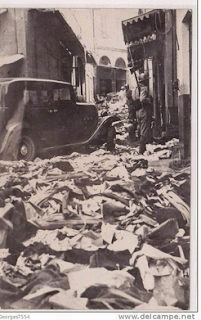

The aftermath of the 1934 Constantine pogrom

In May 1956, there were twice as many fatalities—all of them Muslim. By their own admission, perpetrators were Jewish. Yet the event is nowhere to be found in the Information juive, Algeria’s Jewish newspaper; it’s only briefly mentioned in Jewish narratives of the French-Algerian War. Nonetheless, both Muslim and Jewish witnesses were haunted by the May 1956 battles, the first instance of urban warfare in the war for liberation.

Even the respected lawyer André Chouraqui betrayed his enthusiasm for armed self-defense among Algerian Jews. “Security for our communities above all else,” he intimated in a 1955 letter, “let’s give self-defense to all possible vic- tims.” He related a telling anecdote from his youth: “I remember the joy of Yom Kippur in September 1934 [a month after the riots], when all of the men met at the synagogue carrying revolvers under their prayer shawls.”

Israeli agents were already in action in Tunisia and Morocco, helping Jewish refugees from those areas to evacuate toward Israel. In Constantine, where they entered undercover as Hebrew teachers, their goal was simply to protect local Jews where the French army and police did not (or would not). About 100 members trained with the Israeli envoys. Two of them—Avraham Barzilai and Shlomo Havilio—had served in Egypt, where they had similar secretive cells, which “destabilized Nasser’s government by arming Jewish Egyptians.” A third Israeli operative, code-named “Ibrahim,” directed the troops on the ground in Constantine. His report on May 12 and 13 is the most detailed source of the infamous battle.

Early in 1956, random attacks in the Jewish quarter were increasingly common. In March, a grenade exploded under a table in a Jewish café, disfiguring the legs of ten Jewish people. Early in April, terrorists again placed a bomb under a table at the Bar Nessim, another Jewish bar. Victims sufffering lacerations, unconsciousness, and broken bones caused widespread panic (although only eight men were injured seriously). A large crowd of Jewish civilians pursued the two perpetrators, cornering them in a nearby Muslim café, and “lynched” a few men. Increasingly, civilians carried personal weapons with them. As one journalist explained in late April, “People avoid certain indigène neighborhoods unless they are personally armed.”

A few weeks later, after the murder of a policeman, French police (with help from throngs of local Europeans and Jews) went through the city’s central street, rounding up all Muslim men—a total of about 40,000. Constantine had fallen into a terrible pattern: “Terrorism, counter-terrorism, repression, suspicion, fear.”Europeans (and many Jews, too) supported a strong military response to these attacks on civilians. On May 8, 1956, a crowd in Algiers shouted at Governor-General Robert LaCoste, “No More Reforms! Repression!” After a military parade, the mob chanted, “Long live the army! The Army to power!” Jews felt neglected by the army, but all French citizens (Europeans and Jews) felt that the government ignored their situation. Ibrahim reported that in the spring, after several café bombings, “the rage of the Jewish people peaked.”

Israeli undercover agents reported that they had a premonition that there would be an attack on the Jews on Saturday, May 12. It was the last day of Ramadan (Eïd), and Shabbat. As Constantine Jews—Ibrahim and his wife among them—were leaving synagogue for a drink, they heard a huge blast. Misgeret squads were active and armed; they rushed toward the damage. It was

News reports of the attacks were muddled. It is nearly impossible to conclude who was responsible for the grenade. Officials claimed that a “terrorist rebel gang” fighting for Algeria had infiltrated Constantine; women handed the grenades to male insurgents who would bomb targets around the city.

The London Times reported that the attack came from uniformed rebels, implying that they were an organized force from elsewhere. Another source said that the rebels hid uniforms underneath their clothing. Le Monde reported that the grenade attack was coordinated with a second raid on the city. Adding to the confusion over who attacked the Jewish café, the FLN’s new publication El Moudjahid recounted that the original grenade-thrower was “dressed as a European” and, after throwing the bomb into the café, he fled toward the Jewish quarter. The implication was that the attacker was a French civilian (either Jewish or posing as such), and he planted the bomb to provide an excuse to attack local Muslims. It is also important to note that Jews and Europeans were presented as incompatible—that a Jew could disguise himself as a European and deny something ‘true’ about himself. On the other hand, Ibrahim noted that the perpetrators were “Arabs”—a term that French and Algerian newspapers were uncomfortable using. The Misgeret was importing the term from Israel, just as other Algerian-Muslim activists were cozying up to Nasser’s idea of Arab nationalism and Jewish-Israel conspiracies.

“I ordered [our men] to hurt the Arabs and to rescue and evacuate those [Jews] who were wounded,” Ibrahim reported. A Misgeret squad arrived immediately, chased down the perpetrators, trapped them, and killed them in a barbershop. At the order of a Misgeret commander based in Paris, the squad invaded neighboring Muslim cafés, opened fire, and murdered as many as thirty Muslims that day. “Our men penetrated the neighboring Arab cafés and caused them serious losses,” reported Barzilai in 2005. They “shattered” a Moorish café “with sub-machine gunfire.” Another source states that after the four perpetrators were killed, gruesome combat took over the main streets of the city. Sources are vague about whether the victims were Jewish or Muslim.

After the initial rebels were defeated, Ibrahim wrote, “I kept getting news that a Jewish [armed] mob was planning on breaking into the Arab quarter. I didn’t want things to escalate.” He frowned on the civilians’ “chaotic” system of self-defense. While one Misgeret unit sought after the Jewish mob, another monitored the perimeter of the Jewish quarter. Other squads searched for Muslim rebels inside.

Ibrahim saw the Misgeret’s role as a pacifying one—primarily guarding Jews from “Arabs” (because the French soldiers did not do enough), while protecting Muslims from wayward Jewish mobs. He feared that impulsive violence could escalate into a civil war, especially considering the widespread use of personal weapons. Ibrahim described “middle-aged” and “elderly” Jews who were shooting anyone who looked “Arab.”

In these early years, criminals were known as “rebels,” “assailants,” or “out- laws” (hors-la-loi). Muslims were known as “Muslims,” or inhabitants of the Casbah. After all, a good percentage of Algerian Muslims were not Arab, but Berber. Calling them Arabs, Ibrahim thus imposed categories from the Middle East onto the Algerian context.

Onlookers knew nothing of the Misgeret’s presence, though many intuited that Jews were involved in the repression. Many French sources elided a specific mention of Jews by stating that the bombing’s location was the Jewish quarter.

Others denied any Jewish involvement. A New York Times article claimed that “the Jews themselves took little part in the vigilante shooting that cost thirty-five Arabs their lives.” The London Times described a battle between “the police” and terrorists, “with the civilian populations joining in;” the location of the chaos happened to be in the Jewish quarter. An American- Jewish worker reported that the French army actively recruited jobless Jewish men, one strategy that provoked Jews to attack Arabs.

Rationales for the grenade attack also change according to source. The London Times explained that the attackers went to Café Mazia because its owner would not “subscribe funds toward the rebellion.” The Paris-Presse Intransigent reported that the rebels had heard Jews were organizing in commando groups. Stanley Abromavitch, who was working on behalf of the Joint Distribution Committee, contended that local “Arabs” were angry with local Jews because they believed that Jews were working with French police. Local Muslims demanded loyalty; bombing the café was a harsh warning. Abromavitch revealed that the French authorities had turned Jews and Muslims against one another.

By the end of the day, Ibrahim reported, Jewish morale was very high. He was not shy about claiming a victory—he said that the Misgeret leaders were surprised by their own success. The next day, his pride dissolved into utter shame and embarrassment on behalf of local Jews.

Sunday

Sunday’s story is more difficult to piece together. “It started with the elation of the day before,” Ibrahim wrote, a sense of excitement that was nonetheless accompanied by “edgy” nervousness. By the afternoon, “all was back to normal and the city was crowded,” but “you could feel the tension.” Sometime late that afternoon (accounts difffer: 4:30, 5:30, or 6:00 PM), an offfcer stopped a man who was milling outside an ice cream shop in the Jewish quarter. Many customers thought he was carrying a bomb (no source verified whether this was true). A second officer killed the suspected assailant. The FLN newspaper claimed that the two shooters were not officers, but “French civilians” who encouraged their friends to leave the ice cream store so that they could begin another killing spree, as they had the day before. At the same moment, a second group of “French civilians” approached from a neighboring restaurant, and shot twice: “Le voilà! Le voilà!”The purpose of the shots, according to this theory, was to “create a panicky climate.”

When investigators arrived at the ice cream shop—located in the center of the Jewish quarter—they found six Muslim cadavers and eleven injured bystanders, two of whom were Jewish. According to Ibrahim, most Jews assumed the town’s Muslims were taking revenge for Saturday. The noise of gunshots set off a chaotic shooting spree in which civilians shot at Muslims all over the city, with casualties between 16 and 100. The two Jews who were injured were struck by friendly fire.

In retrospect, some reporters explained Sunday’s attack by describing a “tense” and “nervous” atmosphere. A journalist in Le Monde wondered why the Europeans had been so quick to shoot; “Fear certainly played a part,” was their clipped observation. Another observer attributed the battle to a generalizable

The Muslim-Algerian author and activist Mouloud Feraoun described a devastating shift in the attitudes of the police and soldiers by mid-May 1956. “I hear that people are shot almost anywhere, and that the only effficient form of justice is a quick justice,” he wrote in his journal. “What is the life of a Muslim worth? For the time being, it is worth the burst of a sub-machine gun.” The Jewish mob was following the pace established by French soldiers that month. Muslim lives were simply not worth as much as ‘French’ lives.

There was no denying that Jews were the central perpetrators on Sunday. But Misgeret leaders distanced themselves from Sunday’s events. Even Ibrahim, an undercover agent known only by his nom de guerre, believed there had been a Jewish conspiracy. Ibrahim suggested that some of the city’s Jews were attempting to seize control; he was mired in a power struggle.

“Some Jewish opportunists were trying to encourage fear,” he hypothesized, “inflaming anxiety in the name of self-promotion. They wanted to gain the main posts in the Jewish leadership.” The Jewish Chronicle acknowledged that Jews were “quicker on the trigger” than Muslims.As opposed to Saturday, when squads were reacting to the detonation of a grenade, Sunday was an embarrassment for Ibrahim, and the Jewish population at large. He absolved himself of responsibility, however, blaming “the irrational reaction by a Jewish mob.”

Many onlookers were aware of the role of the Jewish community in Sunday’s counterterrorist action. Even Constantine’s chief rabbi, Sidi Fredj Halimi, made an appeal for the Jews to calm down. “It’s our religious duty to declare that we disapprove of violence, from whatever quarter,” he declared. He knew that many Jews were seeking revenge. Ibrahim thought that Sunday’s overreaction could teach the Jewish community “that they needed to leave defense . . . in an emergency to the professionals.” He vowed that more work remained, and that Misgeret offfcers would be much more careful in the future.

In response to the weekend’s events, French authorities took action in three ways: they issued a strict warning to Constantine’s Europeans; they prohibited individuals from carrying weapons; and they cordoned off the Jewish quarter. Furthermore, Constantine was placed under martial law, a decision that was likely popular among many Europeans, given their demands for more repres- sion and less reform earlier that month.

New York Times photo showing Arabs rounded up and forced against a wall by French soldiers after they had sealed off the Jewish Quarter in the wake of the Constantine battle in May 1956

The French government was infuriated by the Jewish reaction, but authorities did not reprimand Jews separate from Christians. An army general warned all of Constantine’s Europeans against “falling prey to counter-terrorism” and “blind vengeance.” That day, authorities scoured the streets to confiscate individually owned weapons, a form of public punishment, which amounted to a wristslap when compared with the roundup and relentless murders of the city’s Muslims.

When the French military enclosed the Jewish Quarter, were they protect ing or punishing the Jews? Guards forbade pedestrian and vehicular trafffc,

“except to its inhabitants.”

From ‘A Jewish-Muslim battle on the world stage: Constantine, Algeria 1956’ by Jessica Hammerman in The Jews of Modern France (ed Kaplan and Malinovich, Brill)

Leave a Reply