Writing in the Jewish Chronicle, Ben Judah makes the important point that British Jews should read more literature by Israel’s Mizrahi writers. Yes, they should, but the popularity of Oz and Grossman reflects the fact that the make-up of the British-Jewish community is overwhelmingly Ashkenazi. Still, two few publishers are willing to invest in English translation of Hebrew works.

As a secular new year resolution, British Jews should stop ignoring Israel’s Mizrahi writers. Just ask yourself this question: how many British Jews, the same ones with stacks of Oz, Grossman and sometimes even Bialik at home, can name a single Mizrahi novelist or Mizrahi poet?

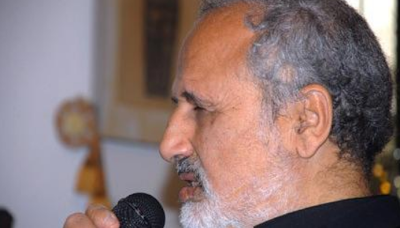

Erez Bitton (Photo: The Poetry Foundation)

This chronic neglect is not just the fault of Jews as readers, but of Jews as educators. This leaves half of Israeli Jews outside of our Jewish imagination. You would never work it out just reading Amos Oz but the family stories of most Israelis are not Ashkenazi-Yiddish epics like A Tale of Love And Darkness.

The exact percentage point is blurred by intermarriage but today just about half of Israeli Jews have Mizrahi roots. These are Israeli stories beginning in Baghdad and Rabat and not just Berlin and Warsaw.

If they really want to feel Israel, British Jews need to start reading more Erez Bitton. The blind poet from Lod, who won the prestigious Israel Prize in 2015, is the Algerian-born master who can take them into the Israel they need to understand. The Israel of the North African aliyah, disorientated and discriminated against in run-down development towns; families who were sprayed with DDT as they reached the promised land.

His poems, like that about Zohra El Fassia, who was “a singer at the court of Muhammad the Fifth in Rabat, Morocco,” can connect us to the other Mizrahi world, of loss.

“It was said that when she sang, soldiers drew knives, to push through the crowds, and touch the hem of her dress,” sighs Bitton. But now, he finds her, “In the poor section of Aktiot C, near the welfare office, the odour of leftover sardine-tins on a wobbly three-legged table, splendid kingly rugs stacked on a Jewish Agency Bed” — imagining herself talking to Muhammad the Fifth in the mirror.

His poems, full of Mizrahi disorientation, can connect British Jews to the feeling of my Baghdadi Jewish grandfather in 1947, that this strange, socialist — “too Ashkenazi” —country was built for somebody else.

Leave a Reply