When the head of the five-person Jewish community of Cairo, Magda Haroun, journeyed to New York to take part in the Jewish Africa conference, the author and reporter Lucette Lagnado interviewed her. The upshot was this piece in the Wall St Journal. (With thanks: Viviane, Carol and Gina)

*Point of No Return comments: with all but a handful of Egypt’s 80,000 – 100, 000 Jews driven out, talk of coexistence and respect between religions sounds a little hollow. The article fails to make clear that 10 of 12 synagogues in Cairo have been designated as Heritage sites under the aegis of the Egyptian ministry of Culture, as Egypt has rejected all offers of partnership with outside Jewish bodies. It seems that a group of interested Egyptians, some with Jewish links, have been enlisted in order to legitimise turning the synagogues into ‘cultural centres’. (The US-based Historical Society of Jews from Egypt, supported by rabbis, has already voiced vehement objections to using a synagogue for purposes other than what it was intended.) Possibly under duress, Magda Haroun has been acting as an agent of the Egyptian government, facilitating the seizure of communal registers and doing nothing to advance demands from exiled Jews for access to their records.

Magda Haroun likes to say she will be the last Jew left in Egypt. She sees it as her mission to prepare for that day, which is why she is obsessed with preserving the remnants of Egyptian Jewish culture. Today, many younger Egyptians don’t know that, in the early 20th century, the country was home to some 80,000 Jews, who lived alongside Christians and Muslims in a flourishing multicultural society.

Ms. Haroun was born in 1952, the year when King Farouk was overthrown and life in Egypt changed dramatically. The Jews of Egypt had been departing in waves since 1948, the year of Israel’s creation, when they suddenly found themselves the object of the rage that so many Egyptians felt over the new Jewish state. Still, Farouk was viewed by the Jewish community as a protector. When Colonel Gamal Abdel-Nasser took over, he made it clear that Egypt was only for Arabs; Jews, even whose families had lived there for generations, didn’t qualify.

Nasser’s government introduced new edicts that confiscated or nationalized private businesses. Jewish-owned companies were forced to take on Arab managers and employees. It became hard for Jews to find work, and financial uncertainty helped to fuel their departure, as much as darker fears of persecution.

But Ms. Haroun’s family refused to leave. Her father, Shehata Haroun, was a charismatic Communist lawyer with strongly anti-Zionist sentiments. He did all he could to stay, including offering denunciations of Israel and Zionism. Still, he was jailed during the anti-Jewish frenzy that broke out during the Six Day War in 1967, when all Egyptian Jewish men between the ages of 18 and 60 were imprisoned, some for years.

When Shehata Haroun was released, he could have left the country—as most of the remaining Jews did—but he insisted that Egypt was his home. Ms. Haroun herself spent some of her adult life living abroad, in Kuwait, Hong Kong, Tokyo and Istanbul. But like her father, she saw Egypt as her home: “I always wanted to return to Egypt,” she says.

Today, there are fewer than a dozen Jews living in Egypt, by some estimates—Ms. Haroun says only four, including herself, are left in Cairo, and another Jewish woman in her 90s died this week. Nobody really knows the exact number, since so many of the Jews who stayed in the country married Muslims or Christians and have kept a low profile. As they aged and lost their spouses, they became, if possible, even more fearful.

But in recent years, some elderly Egyptians—mostly widows in their 80s or 90s—have “come out” to reclaim their Jewish identities. A couple of times a year, they journey shyly to the Gates of Heaven, the main synagogue on Adly Street, to attend a Passover Seder or a Hanukkah menorah lighting. To survive, they receive discreet financial help from the Joint Distribution Committee, the New York-based Jewish relief organization, which has quietly supported the last Jews of the Arab world, sending aid to Algeria and Libya until there were no Jews left to help.

So when Ms. Haroun became president of the country’s Jewish community in 2013, she assumed the role with some trepidation. The community still owned several properties, including schools, synagogues and the vast Bassatine cemetery. The synagogues, many abandoned decades ago, were filled with rubbish and had decaying walls and interiors. But the cemetery was in especially dire condition, vulnerable both to squatters and vandals. After going to visit her father’s grave, Ms. Haroun found the area in disarray, writing in an emotional Facebook post: “Forgive me, Shehata Haroun—forgive me that your place of rest looks like this.”

To tackle the problem, Ms. Haroun made use of a venerable Jewish communal institution: La Goutte de Lait, a school for impoverished children founded in 1918 whose name means “the drop of milk.” Ms. Haroun inserted a new clause in its bylaws suggesting that since there are no longer any Jewish children in Egypt to educate, La Goutte de Lait would instead devote itself to restoring and preserving Jewish institutions throughout Cairo.

This Pied Piper of Jewish Cairo has also enlisted a group of Egyptian Muslims and Christians to help in her efforts. Some, like Samy Ibrahim, Ms. Haroun’s chief of staff, have Jewish relatives. (Mr. Ibrahim’s father, an avowed Communist who converted to Islam, managed to remain in Egypt against the odds, and still lives in downtown Cairo.) Femony Okasha, whose grandmother was Jewish, is another active volunteer. “It is important that people remember how we all coexisted harmoniously in Egypt,” she says. Her work with Ms. Haroun is about emphasizing “values of tolerance and respect.”

The group’s first goal has been to repair the dozen or so Cairo synagogues that are still viable and turn some of them into cultural centers to attract Muslim and Christian—and Jewish—visitors. With American grant money, an Egyptian design firm prepared detailed architectural drawings of Cairo’s dozen synagogues as a first step toward refurbishing them.

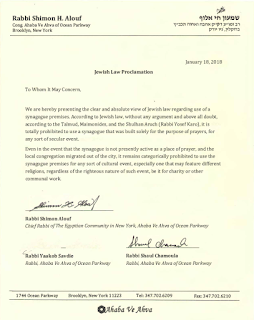

Proclamation by US Rabbis forbidding Egyptian synagogues from being used as social clubs or cultural centres (HSJE)

Another goal of La Goutte du Lait is to create a library to house several thousand Hebrew books that were abandoned when the Jews left Egypt. And of course there is the cemetery. “Every day there are squatters,” Ms. Haroun says. “I want to build a wall to safeguard it.” Ms. Haroun has turned beyond Egypt for support. She spoke in New York last week at the American Sephardi Federation to make the case for rescuing Egypt’s Jewish institutions.

Ms. Haroun has also been working with an Israeli scholar, Yoram Meital, to survey and analyze these properties. Dr. Meital, a professor of Middle Eastern Studies at Ben-Gurion University, has been chronicling what he calls “a very significant attitudinal shift within Egyptian society,” the realization that Egypt suffered from the departure of its Jews. Recently, a group of young people from the once heavily Jewish neighborhood of Daher advertised an evening at the local synagogue, Temple Hanan, which has been closed for decades. Organizers expected 25 people to respond. Instead, 5,000 Egyptians clamored to come.

This embrace of the Jewish past is part of a far-reaching nostalgia for a time that most Egyptians have only heard about from their parents and older relatives—the “golden age” of the early 20th century, when Cairo was a diverse, world-class city. The wider movement includes efforts to restore some areas of Cairo’s downtown, which once boasted grand cafes, cinemas and department stores, many of which were Jewish-owned.

To be sure, the anti-Semitism that Egyptian authorities helped to fuel over decades is far from gone. But after years of hostility and estrangement and war, many Muslim citizens want to reconnect with their former Jewish neighbors. “People say to me, ‘We miss the Jews,’” Prof. Meital says.

—Ms. Lagnado is a reporter for the Wall Street Journal. She is at work on a book, “And Then There Were None,” about what became of the Jews of the Arab countries, to be published by Nextbook/Schocken.

Write to Lucette Lagnado at lucette.lagnado@wsj.com

Leave a Reply