An exhibition celebrating medieval ‘diversity’ in Jerusalem at the New York Met is in fact a tendentious exercise of forced equivalence between the three monotheisms and an effort to claim benignity for Islamic rule. Must-read by Edward Rothstein in Mosaic magazine:

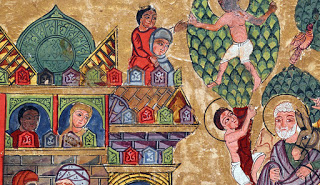

Jerusalem, from an illustration in a Syriac Christian lectionary. 1220, tempera, ink, and gold on paper. (Metropolitan Museum of Art/British Library.)

(…) The Crusaders not only introduced Holy War, they also caused Muslim leaders to distort their own religious teachings by adopting a kind of Holy War in response.

If this argument sounds familiar, it should: a similar argument has gained much traction in recent years among those who regard 9/11 and other Islamist terrorist attacks as a form of deserved blowback for prior Western offenses against Muslims. Intent on its own version of this judgment, the exhibition portrayed the Crusaders as both the single exception to, and the primal cause of any further disruption of, the multicultural paradise of medieval Jerusalem.

To accomplish this sleight of hand required some significant historical manipulation and revisionism. As the exhibition described it, for instance, the ecumenical rebuilding of Jerusalem under the Fatimid caliph in 1130 was necessary both because of earlier earthquakes and because of the “malfeasance” of the preceding caliph. Malfeasance? Earlier in the century, that caliph had ordered the destruction of all churches and synagogues in his Islamic empire; in Jerusalem alone, thousands of buildings may have been destroyed; the Church of the Holy Sepulcher was razed. Why was the nature of this malfeasance not mentioned? No doubt for the same reason that no mention was made of the Muslim massacre of Christians in Jerusalem in the 10th century—long before the Crusader conquest. As Eric H. Cline points out in Jerusalem Besieged: From Ancient Canaan to Modern Israel:

When the Byzantine armies won a series of victories in the field against the forces of Islam toward the end of May 966 CE, the Muslim governor of Jerusalem—who was also annoyed that his demand for larger bribes had not been met by the patriarch of the city—initiated a series of anti-Christian riots in the city. Once again churches were attacked and burned in Jerusalem. The Church of the Holy Sepulcher was looted and was so damaged that its dome collapsed. Rioters even killed the patriarch, John VII, who was discovered hiding inside an oil vat within the Church of the Resurrection.

In 1070-71, the Turkic emir Atsiz ibn Uvaq al-Khwarizmi captured the city, and six years later he murdered 3,000 Islamic rebels who had plotted against him, including some who had taken shelter in the al-Aqsa mosque. En route to Jerusalem in 1187, Saladin, founder of the Ayyubid dynasty, slaughtered Christian communities throughout the Holy Land. Later, in 1229, despite the city’s alleged centrality to Islam and just decades after the fall of the Crusaders, a subsequent Ayyubid ruler offered Jerusalem to Frederick II, the Holy Roman emperor, in return for military assistance against a Muslim rival for power. In 1244, another Ayyubid ruler lost control of Jerusalem to Khawarezmi Turks who murdered much of the city’s population. In 1263, almost at the center of the era covered by the show, the Mamluk general Baibars attacked Acre and other cities held by Crusaders. As the historian Simon Sebag Montefiore relates in Jerusalem: The Biography, Baibars “received Frankish ambassadors surrounded by Christian heads, crucified, bisected, and scalped his enemies, and built heads into the walls of fallen towns.”

Nor did brutality, some of it intra-Islamic, stop there. Sacking, warfare, disruption, and rebellion extended all the way through the 14th century—the last span covered by the exhibition and hailed as the apex of “stable reign”—which featured a Mamluk sultan installed at the age of ten and later strangled in a coup and numerous other revolts and upheavals, a chronological account of which would be impossible to relate without seeming to have concocted an extravagant version of the very opposite of the exhibition’s claim for it.

The Absent Presence of Jews: When the Iberian Jewish scholar Abraham Abulafia visited Palestine in 1260, he could get no closer to Jerusalem than Acre in the north because of the ceaseless fighting. Seven years later, the visiting Iberian eminence Moses Naḥmanides succeeded in making his way to the city and found there only two surviving Jews (or possibly two surviving Jewish families).

And this brings us to the subject I’ve largely postponed till now: namely, the situation of Jerusalem’s Jews. Although Jews and Jewish artifacts were certainly present in various ways throughout the exhibition, their presence was an exceptionally vague and fleeting one, functioning mainly to round out the museum’s picture of three supposedly equal and equivalent monotheistic faiths coexisting in some kind of balance. Thus, if Islam was represented by the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa mosque, and Christianity by the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, Judaism had what the organizers describe as “The Absent Temple.” Solomon’s Temple, we were told, had been a “vast complex that housed the Ark of the Covenant”; centuries later, after the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans in 70 CE, the site became “the focus of Jewish devotional practice both locally and from afar.” Jews, the exhibition noted, would visit Jerusalem “to mourn the destruction” of the Temple and to pray for its rebuilding.

How to present this absent Temple? Instead of artifacts connected to the structure (as in the gallery assigned to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher), or objects from other regions allegedly similar to those in the structure itself (as in the gallery assigned to the al-Aqsa mosque and the Dome of the Rock), the gallery assigned to the Temple offered medieval images and illustrations evoking either it or Roman-era Jerusalem more generally: a painted menorah in a 13th-century Italian manuscript of the Bible, an image of Jerusalem’s Gates of Mercy in a 13th-century maḥzor from Worms, enchanting wedding rings from the 14th-century Rhine valley of which one was decorated with a three-dimensional golden model of the Temple.

The show’s forced equivalences among the three monotheisms thus led to a severely skewed perspective. The Church of the Holy Sepulcher was materially substantial in the exhibition, possessing both a history till this day and a continuous (if periodically rebuilt) physical presence. The al-Aqsa mosque was granted an almost sublime aura as if it dwelled outside of history even as it, too, like the Dome of the Rock, remains very much physically present on the Temple Mount. The “absent Temple” was left as a ghostly image from the distant past, with no substantial reality.

Judaism’s presence in Jerusalem, in other words, was not just vague but itself an absence—a “poignant absence,” as the catalog puts it, especially when contrasted with the “richly appointed Christian and Muslim shrines of medieval Jerusalem.” But this poignancy is based on a false parallel. What, after all, was the meaning of Jerusalem for Jews? It was a meaning reflected not in art or artifacts of the kind that might fill galleries at the Met but in a millennium and more of liturgical, theological, philosophical, and legal texts bespeaking an unbreakable attachment as well as in sporadic, short-lived moments of messianic speculation and movements of return.

And that’s only part of the problem. Almost everything we know about Jewish life during the period of Christian and Islamic rule is at odds with the exhibition’s desire to evoke a wondrous world of diversity: a “college town” in which learning, debate, and cross-cultural fertilization conjoined in a thriving renaissance. Jerusalem in the 11th through the 14th centuries could not be considered a center of Jewish learning or indeed of Jewish life. There were such centers elsewhere, but in Jerusalem the community was not thriving at all; instead, it lived subject to extraordinary pressure.

For a minor part of the exhibition’s four centuries, Christians ran the city; for the rest, it was ruled by Muslims of one dynasty or another. As for the Jews, the best that can be said is that they survived. And when Jewish migration to the Holy Land picked up under Mamluk and later Ottoman rule—often as a result of persecutions in Europe—the way Jews could get physically close to the location of the “Absent Temple” was by seeking permission to pray along the Mount’s Western Wall. Everything adjoining the Wall was owned by Islamic authorities, and shops and dwellings proliferated there up through the period of the British Mandate. Not until after the June 1967 war did Israel clear the area in order to provide access to a holy site from which Jews had long been restricted and, for decades of Jordanian occupation, forbidden. Such was the ecumenical nature of medieval Jerusalem and its enduring heritage into the 20th century.

A letter from Maimonides, written in 1170 from Egypt, tells all. It was displayed in the gallery devoted to “The Diversity of Peoples”—presumably because it was written in Arabic using Hebrew script and involved an international issue. But its real “diversity” lay in the unique issue under consideration: the letter was written to raise funds needed to rescue Jews who had been abducted and were being held for ransom. In another letter on display, from 1125, the famous poet Judah Halevi, writing from Toledo, Spain, expresses his longing for Zion. But this letter, too, was related to the same matter, as the catalog informs us: the poet, as a community leader, “was involved in fund-raising for the ransoming of Jews taken captive by Crusaders.”

But it wasn’t just Crusaders who did the abducting. Though we would not have learned this from the exhibition, such kidnappings of “infidels,” including Jews, were for centuries commonplace Islamic tactics (and a source of many slaves)—so common, that an entire corpus of Jewish law was devoted to the means of responding to these extortionist demands: an aspect of “multiculturalism” that seems to have made a bad fit with the exhibition’s confident enthusiasms.

Not only was no notice taken of these matters but, among the three faiths, a tendentious impulse was at work in the exhibition to celebrate Islam above the other two and, in particular, to claim benignity for Islamic rule.

This sometimes went to absurd lengths. The catalog, for example, cites a cloth merchant commenting in 1488 on the styles of dress in Jerusalem and noting, for example, that “Moors wear white, with head wraps of fine cotton or toile de Hollande.” The hat of the Mamluk, he further states, was red, secured by a white cloth with a striped border. As for Jews, they wore yellow; and as for Christians, blue and white linen. The roster is taken as further evidence of diversity, in this case sartorial—in oblivion of the fact that where Jews and Christians were concerned, the color of items of clothing was regularly mandated by Islamic authorities who treated these populations as dhimmis, lacking important rights and required to pay additional taxes. If Jews were wearing yellow, it was likely not because of their taste in color.

Leave a Reply