As the Yemenite Children Affair rumbles on, Yaakov Lozowick, former Israeli state archivist, writes in the Tablet that the staying power of the issue has more to do with emotions than facts. The recently released archive documents, argues Lozowick, corroborate the conclusion that there was no official policy to kidnap babies from Israeli hospitals.

I chose Haim’s file at random. You read these testimonies—one, then another, then a dozen, then hundreds—and you understand why the grandchildren won’t let go. It’s heartbreaking.

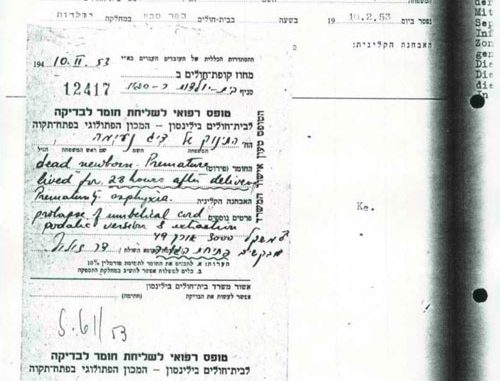

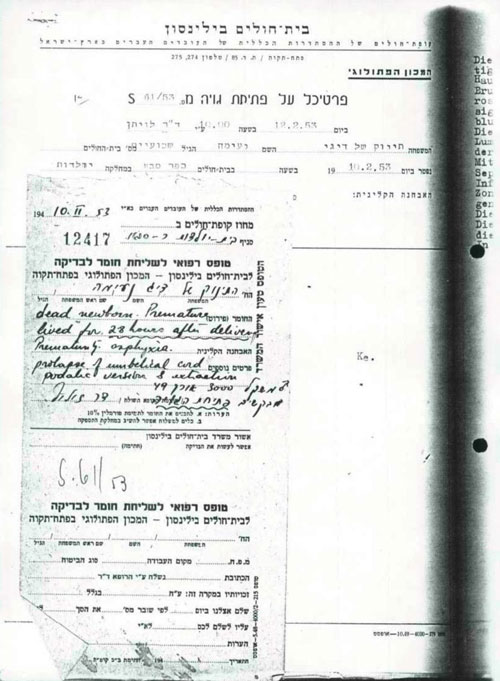

But that’s not all that’s in the files. There are lists of patients confirming who was where; and who died when; and who was buried precisely when and where. Sometimes sections of the lists are copied into the case files of individual children (in Haim’s case, here). Sometimes there are specific, individual documents such as hospital reports by doctors, or death certificates. In Haim’s case there’s a detailed paper trail, from the local clinic in Rosh Ha’ayin all the way to his grave. It includes the initial fear of polio which caused him to be sent to the hospital, various medical reports and lab results at the hospital, an official death certificate, and the specific burial license in the Petach Tikva cemetery. Since we used an advanced tagging system, the public can research by subjects, such as prohibiting visits by parents, or medical personnel.

All three investigating committees have been castigated by families and activists for being sloppy, or perhaps intentionally negligent. One can follow the investigators in their daily work, here and here, for example. So far as I could see, they seem to have worked methodically and with great professional integrity.

There are no documents that tell or even hint at a governmental policy of kidnapping children for adoption. Not one. Had there been such a practice, there would by necessity be hundreds or thousands of elderly dark-skinned Israelis who grew up in light-skinned families in the 1950s and ’60s. These people don’t exist. So, the activists claim, the babies were exported and sold to rich and childless Jewish families in America, or perhaps elsewhere. The archives contain not a shred of evidence for this claim, either.

Over the past three years I have sat in public discussions of the Yemenite Children Affair at the Knesset and elsewhere; I’ve followed the significant media attention given it; I’ve maintained personal contact with many of the main activists; I’ve watched three cabinet discussions. And while we were preparing the archives, I personally looked at hundreds of files and talked to the staff as they looked at thousands. From here on, I’m speculating, based on what I’ve seen, heard, and learned.

The stubborn staying power of the Yemenite kidnapped babies story comes from emotions, not historical data. There is none, and never was any—which is why opening thousands of files never made a dent. The activists merely moved their focus: The Big Secret must be in the Mossad’s files; or WIZO’s files; or in files that had been destroyed. As I was leaving my position a few months ago, they were speculating we had merely pretended to open everything while in reality opening only the “harmless” files.

Yet many family members will admit, at least in private, that what they are seeking is not evidence of kidnapping, but closure for the deaths of their loved ones. They want to see a grave, not a scanned image of a Xeroxed copy of a list of graves from the 1970s. They want explanations for the demeaning behavior of arrogant medical staff and bureaucrats who brushed them off, and otherwise treated them as inferiors, or at least as bothersome. If you assume—as I’m inclined to do—that the overworked staff trying to deal with a tsunami of immigrants in a poor country were normal people, and sometimes even idealists, it is also easy to imagine the callousness, and obtuseness, and even contempt, with which the young parents were fobbed off. Some of it can be explained by pressure, some by prejudice. And some, perhaps, by the need indeed to hide a secret—just not the one the activists seek.

There are more than 200 files with information about autopsies. My personal opinion is that these may contain an important key to the entire story. Admittedly, while we were working on the files I asked my entire staff to look for a smoking gun and we didn’t find it. But there is circumstantial evidence that many of the deceased infants had autopsies performed on them. The medical staff was distressed by the high death rate, which was especially high among the Yemenites, and they sought explanations. The body of an infant after an autopsy has been performed is not something one wishes to show grieving parents, certainly not religious parents from an undeveloped country who don’t speak any of your languages, and who never gave their permission for the bodies of their dead children to be cut open.

There was no crime, but there was a sin. All sides were unfamiliar to each other and overwhelmed, in different ways, by their circumstances. Those in power did their best, with scant resources—and scant regard for the emotions of the immigrants they were tasked with helping. The immigrants were also doing their best—and have bequeathed their traumas to their more confident, better-positioned descendants.

Leave a Reply