In tribute to Ezra Laniado, the author of one of the few books about the Jews of Mosul, Dena Attar in The Jewish Chronicle recalls the suffering of this small community in the north of Iraq. The period before their mass flight to Israel was replete with threats, extortion and anti-Jewish agitation.

Mosul, Iraq’s second city, was formerly part of the Ottoman Empire. Jews were conscripted into the Ottoman army from 1908 and many did go to fight, with about 100 joining the “matches” battalion, nicknamed when they had to hold up matches to find their way to the frontline at night.

Many other Jews from Mosul, like my grandfather, escaped conscription and probable death by going into hiding in local Kurdish villages or in cellars, aided by the community who stalled Ottoman officials searching for them. One story even told of a father retrieving his conscripted son from the Syrian city of Homs as the Ottoman army was in such chaos nobody could stop him.

The war brought extreme suffering, especially during the famine of 1916-17 when the army seized all of Mosul’s food supplies. Two rabbis, Hakham Yahya Hamo and Hakham Eliyahu Barzani, who both sold spices, perfumes and herbal medicines, raised money to feed the starving population. One man who sold his home and entire possessions to feed his family but was still destitute went to “Babylon” (Baghdad) to plead with Rabbi Dangoor to help famine-stricken “Assyria” , lamenting “there is no pity and there is no mercy and hunger is outside every door.”

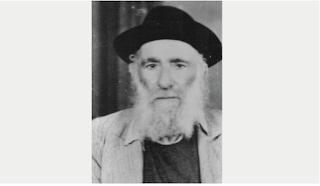

Haham Yahya Hamo, Dena Attar’s great uncle: raised money to feed starving Jews in 1917

The British were welcomed to begin with as one of the first things they did was reopen the grain barns, but nationalist feeling in the 1930s following Iraq’s independence was fiercely anti-British and becoming influenced by antisemitism. In April 1939 when the young king died in a car accident but was rumoured to have been assassinated, a crowd gathered in Mosul to attack the Jewish quarter. The rioters were diverted at the last moment, storming the British consulate instead and murdering the consul George Monck-Mason.

Two years later during Rashid Ali al-Gailani’s pro-German regime the Jewish community was again terrorised with threats and absurd spying allegations. Many Jews were searched, imprisoned and tortured. The military governor Kassem Maksoud summoned 14 community leaders and attempted to extort a huge sum from them in gold coins, beyond what they could possibly raise. Eyewitnesses recalled that he was unable to look them in the eye when he claimed this was to guarantee their loyalty.

One informant recalled the day news of the June 1941 Farhud in Baghdad — in which hundreds were robbed and killed — was intercepted by Habib Salah Shaoul, a Jewish telegram worker in the post office. Shaoul decided at the risk of his job to shelve the telegram and warn the community rather than passing it on. That delay gave the Mosul community a chance to prepare and defend themselves, averting an attack.

There were a few years when conditions in Mosul improved but in the late 1940s Jews from nearby Kurdish villages began leaving after numerous threats and murders, and anti-Jewish agitation intensified at all levels. The old system of Kurdish Jews relying on local chieftains for their livelihoods and protection was breaking down.

Mosul’s one Jewish MP, Sasson Tsemach, had made a point of cultivating good relationships with Christian religious leaders. In 1946 he interceded in customary informal style with a Christian patriarch to get justice when a large number of Jewish pilgrims travelling to the tomb of Prophet Nahum in the Kurdish Christian village of al-Qosh were attacked and robbed. Tsemach was only partially successful as local people threatened reprisals when the perpetrators were identified and arrested. The community had little recourse to justice when police and army officers in Mosul harassed them, raiding homes on flimsy evidence and jailing anyone they alleged was a Zionist agent.

The community was forced to pay bribes to get prisoners released. Mail between Iraq and Palestine was legal before 1948 but possession of mail from Palestine, and later from Israel, became a crime. As letters took time to arrive, emigrants from Mosul and Kurdistan had already written asking after friends and family. When such letters were intercepted, houses would be searched and people arrested and interrogated.

Shoshana Arbili, who eventually became a member of the Knesset, wrote from Israel to Raful Chai Hamo asking after his sisters and her friends. One of them, a child named Lillian mentioned in her letter, was detained and questioned for hours in the police station. Once it seemed they had no future in Iraq, Mosul’s Jews endured a long wait for transport and permission to leave.

Entire Kurdish Jewish communities driven from their villages were stuck in transit in the city for a year, housed in school and synagogue halls. When they ran out of food, and fuel Ezra Laniado and his friends raised funds to support them. Mosul’s Jewish population was a tenth the size of Baghdad’s, less wealthy and less influential, but their loss of homes, businesses, property and culture was as traumatic and perhaps even more complete.

Leave a Reply