Turkey feels like a dictatorship hiding in plain sight, writes Annika Rothstein in this insightful piece in Rebel. Yet few Jews would have voted for anyone in the recent elections other than Prime Minister Erdogan, believing he alone would ensure stability. No Jew has ever been arrested, but fewer identify publically as Jews. ‘It is a slow suffocation of Jewish existence, as opposed to an outright shot to the heart’. (With thanks: Michelle)

Nisim’s grandfather suffered under the Turkish “wealth tax” that as instituted in the early 1940s, aimed at Armenians, Jews, Greeks and Levantines. The official reason for the tax was to amass funds for a possible entry into WW2, but in reality it was a way of throwing Turkey’s non-Muslims into financial ruin and despair.

Because of his inability to pay the massive dhimmi-tax, Nissim’s grandfather was thrown into a prison camp and his grandmother borrowed money from Muslim bankers in order to get him out. Once freed, he was forced to work several jobs for the rest of his life, just to manage the payments, and all the untold stories of this hardship is reflected it Nisim’s eyes as he stands at the foot of his grave.

I take a picture of Nisim but he asks me not to post it on social media.

“The government is already monitoring me, and I don’t want to give them an excuse to say that I am some sort of terrorist, speaking ill of Turkey or complaining about our history.”

I try really hard not to show the anger I feel at his words; anger at how little has changed since the dhimmi-laws and the outright persecution, and at how the Jews of this land are still locked in a prison of fear and silence. Feeling that my reaction would somehow be disrespectful or patronizing I walk next to him in silence, reading each name out loud to myself; making sense of the words as the outside world befuddles me.

During Ramadan when I was there, the pace of the city is sluggish in the unrelenting heat. Nisim and I go to a nearby kosher restaurant, the only one around, and Nisim shows his ID-card at the unmarked door, revealing the word “Musevi” (Jew) in bold black letters. The owners of the otherwise empty eatery treat us like royalty, and while they speak no Hebrew they chatter in fluent Ladino, one of the few remnants of a time that was.

There is a warm familiarity between the two of us, despite the fact that we didn’t know each other’s names just a few days ago. Regardless of geography, age or our levels of observance, we are just two Jews sharing a meal, cooked according to the rules of our ancient faith. Right below the restaurant lays a small but ornate synagogue, and as we walk through it we are approached by the curious keepers of the keys, asking for our names and ID. This is the case in every Jewish institution in this city; the doors are unmarked but heavily guarded and usually, getting in takes more than one form of verification.

That feeling is everywhere – the low-level fear and hostility. Turkey is a deeply conservative country, shrouded in modern attire. While there may be plenty of scantily clad European tourists on the streets of Istanbul, I am told not to walk alone at night and definitely not wear my Magen David necklace or tell anyone that I am a Jew. Having already spent time in Iran I am surprised at how this place feel more menacing, somehow, perhaps because the world is in agreement on what Iran is, whereas Turkey still is able to play the role of country among countries while its leadership does away with basic rights and freedoms. It feels like a dictatorship hiding in plain sight, jailing and killing minorities and journalists while millions of tourists take selfies on the beaches of Antalya.

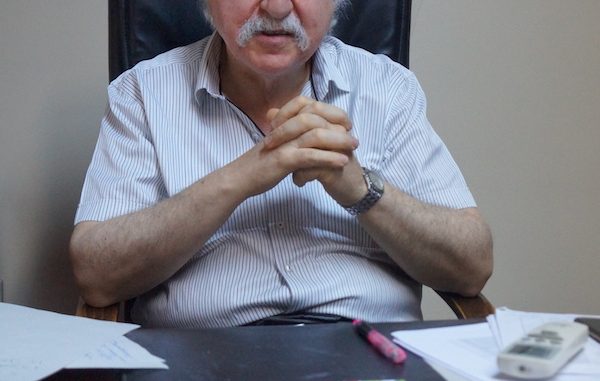

Erdogan has achieved stability, says Turkish Jewish author Rifat Bali when I meet up with him in his downtown office. He agreed to meet with me after a great deal of coaxing, and as soon as I walk in I can sense a tension coming off of him, in action as well as in words:

“Erdogan is the best option for the Jews in this election. I mean, what options are there? Anything but Erdogan would mean chaos, and chaos has never ever favored the Jews.”

Rifat Bali: ‘Turkish Jews live a dual life’

Nissim is sitting next to me and he boldly interjects in disagreement, receiving little but a scoff for his trouble. Mr. Bali assures me that the Jews will not be persecuted under Erdogan and that, as far as he knows, no Jew has even been arrested. When I ask him about the President’s constant and virulent anti-Israel rhetoric, Bali shrugs and says that this is a language that means very little in actual terms in this part of the world:

“Turkish Jews live a dual life, where we know not to put Israel on the forefront, but keep that private. The Turkish Jews that remain here are well off, they live good lives, and they know how to survive in this environment where very few Turks carry the baggage of rational thought.”

And he is not wrong, at least not about the last part. The remaining Turkish Jews have developed excellent survival skills, and very few still carry their Jewish family names but have adapted and changed to accommodate their surroundings. There is still more of a Jewish framework here than in my native Sweden – such as several kosher butcheries, three kosher mikvaot and at least three daily minyanim – but the power of self-censorship has set in long ago and fewer and fewer keep kosher, use the Mikve or partake in any other form of observant Jewish life. It is a slow suffocation of the Jewish existence, as opposed to an outright shot to the heart.

As Turkey approaches their general elections, Jews are keeping well out of the way of the public debate and focusing on staying off the radar. Recent events, such as the embassy moving to Jerusalem and violent riots in and around Gaza, has raised the threat level and caused discord within the community, as many now feel that they are being targeted based on Israeli and American policy, despite doing their best to slip into the shadows.

Nisim and his family listen to me as I sing the “Birkat Hamazon,” and afterwards we retire to the living room with the traditional glass of chai and delicate plates, overflowing with fruit. We are in a Jewish bubble now, a place of comfort for all of us, and very little reminds us of the troubling status quo that looms outside those doors. By nightfall the next day, I will be leaving, and the family will stay in a country that for decades has done its best to force them out. I am as impressed by their dignity and tenacity as I am heartsick for their peril, and as a fellow diaspora Jew with centuries of roots in a land that treats me like a stranger I fully understand why they feel they have to stay and see this through.

Perhaps Rifat Bali was right; maybe the leadership of Turkey doesn’t matter to the Jews, as there are no leaders left who would protect them. To seek the status quo, though, is a fallacy, because Erdogan will likely not rest on his laurels if he lives to fight another day. Mr. Bali laughed at me when I asked him if Turkish Jews faced a possible expulsion under an even more totalitarian Erdogan rule, saying that this was typical hyperbole, emanating from an ignorant foreign media. But after a week in Istanbul I see that there are many ways to expel a people, or to simply make them disappear. Nisim’s grandfather is proof of that, having been taxed out of house and home and penalized to near assimilation. Today’s Turkish Jews are fading into the woodwork, despite thousands of years of glorious history, and while the Turkish government may claim it is done by choice it is clear to me that this is done out of heartbreaking necessity.

Leave a Reply