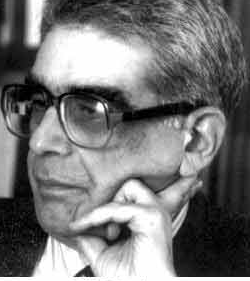

Baghdad-born Elie Kedourie is one of the most under-rated of historians, yet he foresaw what Middle East experts today now acknowledge with despair: that the post-WWI newly-independent Arab world would be a disaster for society and minorities. On the 50th anniversary of the publication of Kedourie’s The Chatham House Version, Robert D. Kaplan has this long but worthwhile read in National Interest:

Kedourie’s essential diagnosis of Great Britain’s Arab policy in his lifetime was that the British Foreign Office’s awe of an exotic culture, combined with the “snare” of a misunderstood familiarity towards English-speaking Arabs—who used the same words, but meant very different things when discussing such issues as rule-of-law and constitutions—led to a profound lapse of policy judgment: towards which, one must add guilt regarding the post-World War I border arrangements that allowed for, among other things, a Jewish national home in Palestine. In the minds of this naïve generation of British officials, once Zionism and imperialism could be done away with, the Arabs would enjoy peaceful and stable institutions.

Fifty years ago, Kedourie countered with what in recent decades has since become a commonplace: that neither imperialism nor Zionism were the problems. As he put it, it is only a “fashionable western sentimentality which holds that Great Powers are nasty and small Powers virtuous.” In any case, he continues, even without imperialism and Zionism other outside powers would naturally work to involve themselves in this vast, energy-rich region as part of the normal course of history. The West was a problem, certainly, but in a different way than late British colonial officialdom and some of their American Cold War successor-acolytes had imagined it: Westernization and modernization were only amplifying the coercive, illiberal power of newly independent Arab regimes themselves.

Consequently, the nascent Arab middle classes were even more dependent on the goodwill of those vicious new regimes than they had been on the colonial powers. Indeed, everything from import licenses to securing jobs to school admissions required a silent pact with the authorities. And when oil wealth was suddenly added to the sociological fire of a falsely Westernizing Arab world, as Fouad Ajami (echoing V.S. Naipaul) explained: inhabitants of the great cities of the Middle East began experiencing the West only as “things” and not as “process,” importing the “fruits of science” without, as societies, producing them themselves. The results were sophisticated milieus, West Beirut being one for a time, of “Western airs and anti-Western politics.”

The Arab youth were especially dangerous, Kedourie unsentimentally observes: full of “passion and presumption,” they possessed the techniques of Europe without intuiting the cultural processes that had made Europe what it was. They hated their fathers’ world, and saw utopia rather than civil society with all of its messy backtracking, compromises, and checks-and-balances; thus, they paved the way for replacing Arab nationalism with Islamic fundamentalism—a phenomenon of a rapidly urbanizing Middle East, where the traditions of the village have been weakened and must be fortified anew in more abstract and ideological form.

The despair with which the class of Middle East experts in Washington now view the region is one that Kedourie arrived at long ago, and not cynically. Rather, it came about through painstaking historical research.

Leave a Reply