Tunisia came under German occupation for six months in 1942. Most able-bodied Jewish males were sent to forced labour camps and Jewish families had to shelter from nightly bombing raids. Max Galula, then a child, recalls those difficult times. (With thanks: Freddy Galula via the Musee Juif tunisien)

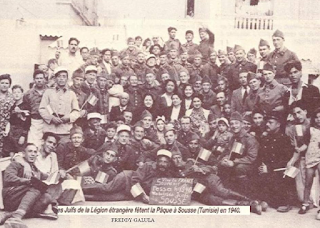

Soldiers of the French Foreign legion celebrating Passover at Sousse, Tunisia in 1940 (Photo: Freddy Galula)

They say a war breaks out like a thunderbolt, suddenly.

Though I was a child, I could see that it was coming: Vichy’s anti-Jewish measures, my father’s resulting dismissal, and in particular Hitler’s thunderous speeches on the radio, from 1938 on.

Clearly we could not understand his yelling, but it made my uncle Victor say, ‘we’re done for’. Recently I read a story about the Vilna ghetto and found this sentence: ′′ When I switched on the radio on June 22th, a hysterical howling in German leapt out at me, like a coiled viper. ”

The six months of German occupation were, for some unfortunates, a real drama. From Tunisia, hostages departed by plane for the death camps. (The plans for our own death camps existed, but there was no time for them to become operational).

How can one not mention the death of my friend’s brother, Georges Mazouz? He was being seen for an orthopaedic problem at the Charles Nicole Hospital when he was picked up and pushed into a column of Jewish workers.

On the Internet recently one worker told us of the aftermath of this tragedy: workers took it in turns to carry the unfortunate fellow, through the rain, then the mud, for endless kilometers, until a German put a bullet in his neck. Let’s not forget those who died in our villa in La Goulette either.

The wall chart of Europe with its small flags, sustained us; the Nazis had broken their backs in Stalingrad.

After a few weeks, my Dad returned from his work camp. One of his companions of misfortune had a genius idea. He asked everyone to scratch their skin until they drew blood. Nothing scared the Germans more than epidemics and, hearing the words typhus and ringworm, they gathered the workers together and and sent them all home.

We children stayed carefree yet fearful of the nightly bombardments. Hunger often tormented us and was hardly relieved by the oily doughnuts, bought after standing in a two-hour queue at five am.

Families had been reunited. The Cacoub family, whose building was bombed, joined us at my grandmother Tubiana’s , neighbours and cousins.

We slept on the floor, fully dressed and, as soon as the sirens went off , thirty shadowy figures pressed into the stairwell, towards the entrance of the building, which had no basement. Until the relief of the second siren, the place seemed to amplify the noise, making it seem that bombs were always falling on our heads.

The realisation hit me, after being buried for so many years in our unconsciousness, how serious the situation really was.

When the alerts were over, the memory comes back to me of our foolish game: We were watching out for the moment that Aunt Julie, who was a little snobbish but oh so elegant, even at three in the morning, would go up the stairs to spit. How we laughed at her disgusted expression when she saw the glutinous blob in the palm of her hand.

In our new street, there was the Protestant church in Tunis, an Anglican bookstore, with bibles in window (more about this later) , and our synagogue, which the Boublil family had set up in a laundry room, located on the terrace of a building they owned. It was a simple place but elevated by its elderly faithful, including my dear grandfather whose orthodox religion was so far removed from current practice.

During the major Jewish festivals, the Boublil relatives not living in our neighbourhood attended.

Moving house actually gave me a second home – my maternal grandmother Tita’s, located close to ours. Her apartment was always wide open to me( as it was to our Tubiana cousins, her neighbours). It was on the first floor of an old caravanseral. Its courtyard, prior to sheltering poor Italians, served as a stable. Her front door opened out on to a galleried space overlooking this courtyard, which became all our families’ Succah (and at the end of the festival, the palm trees, rid of their dry leaves, served us as swords). .

For me it was my observation post.

As if in a Murnau movie; I saw an undertaker with a small coffin under his arm, with no one to accompany him (indeed, it was usual to bury a newborn baby, who had died in its first days, in a place that would remain unknown to the mother).

I saw our neighbour Jacques leave for the army in 1940, wearing his intriguing gaiters, all gung-ho and smiling, and shortly afterwards, his widow.

I saw an Italian girl in the yard showing us her ass…. Rounding up the Jews gave her such pleasure!

I saw the rather silly son of the Italian shoemaker bouncing clumps of bread at the Jews’ apartments, aiming at open doors in order to destroy Pesah efforts to eliminate every crumb.

There I saw, on the eve of the feast (of Eid al Adha) the sacrifice of the sheep.

Leave a Reply