Increasingly, the Farhud – the murderous pogrom which claimed the lives of 179 Jews in 1941 – is being recognised as a major trigger for the mass exodus of the Jews of Iraq. Writing in Haaretz Dor Saar-man generally does a good analysis of the anti-Jewish currents leading up to the pogrom but it is marred by inaccuracies. But it is not true that Jews did not suffer prior antisemitism. In 1889, an anti-Jewish riot swept Baghdad. An anti-Jewish ruler, Daoud Pasha, incited anti-Jewish pogroms in the 19th century. (With thanks Yoram, Lily)

The attack on the city’s flourishing, peaceful Jewish community is usually referred to as the trigger for the Iraqi aliyah to Israel. But seldom is the question asked: How could such a pogrom have occurred in the first place in Iraq – a place where Jews had lived in peace for centuries, a country that did not seem to suffer anti-Semitic norms?

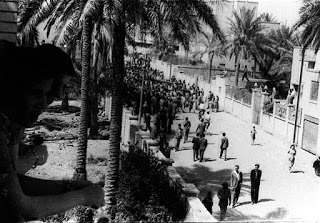

Jews queuing up to register to leave Iraq at the Messouda Shemtob synagogue, Baghdad in 1950

An examination of the historical background reveals the Farhud’s causes: the opposing interests of the Iraqi government and the British Empire, Nazi Germany’s influence, internal Arab movements, and a struggle between groups of Iraqi intellectuals. The unfortunate Jews were caught in the middle.

Historian Nissim Kazzaz has researched Iraqi Jewry and managed to put the Farhud in its historical context. Until the 1920s there was no significant evidence of anti-Semitism in Iraq. (Not true, see intro above – ed) Old restrictions from the Ottoman era were abolished during the 20th century and the establishment of the British Mandate after World War I soon changed the Jews’ situation for the better.

Yet World War I had other outcomes as well. The Iraqi elite were introduced to “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” a forged text that was partly translated from the original Russian into Arabic. New movements were rising in that period in Iraq, some of which argued that as long as the Jews did not hold national inspirations, they were part of the Iraqi nation without obstacles.

But other movements, such as Al Istiklal, had a different opinion. Perceiving the Iraqi nationality as Arabic and Muslim, they would not include religious minorities such as the Jews. Formally, after Iraq received independence from Britain in 1932, the Jews were considered Iraqi citizens, but some voices always argued against their integration.

At the same time, the world was going through profound changes. Fascist leaders rising in Europe such as Hitler and Mussolini had supporters among the Iraqi elite who resented the British. Even after independence, the British still expected certain privileges, especially in the transfer of goods through Iraq, which the Iraqi nationalists would not yield. They insisted that Iraq should establish a close relationship with Germany instead of being exploited by Britain.

Meanwhile, Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” and speeches were translated into Arabic, and German educators came to Iraq to spread radical anti-Semitic propaganda (in fact there were enough ‘homegrown’ educators, such as Sati al-Husri and Sami Shawkat – ed) . Iraqi newspapers went all the more pro-German, especially after 1939. They asserted, for example, that Iraqi Jews and the Zionists were one and the same, that world Jewry was scheming to ruin the glorious nation of Iraq, and that Jews must be banished from public life. (This happened before 1939 – ed)

With help from the Germans, the Al-Fatwa religious movement was founded; it espoused the keeping to strict Islamic rules and practices by all citizens, and it was inspired by the Hitler Youth( I think the author is confusing the Futuwwa religious movement with the pro-Nazi paramilitary youth movement in Iraq of the same name – ed). At a certain point, all students and teachers were forced to join the movement – including the Jews. In 1939 the grand mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, settled in Iraq (he was expelled from Palestine by the British – ed), lobbied for the Germans and spread hatred against the Jews.

The tension boiled over on April 1, 1941. Until that day Iraq did not assist the British, but it also did not assist Germany directly. Eventually, Prime Minister Rashid Ali decided it was time to switch allies (in fact al-Gaylani was anti-British since the 1920s and 30s). He launched a coup against the pro-British officials (there had been repeated failed coup attempts between 1939 and 41); he then announced that Iraq would no longer assist Britain with airplane fuel, and even sent military forces to British bases in Iraq. By the end of April, the British had attacked the Iraqi army, which was now backed up by Luftwaffe pilots.

In May, the British fought the German-Iraqi force and had help from groups like the the Irgun Jewish militia based in British Mandatory Palestine. In one operation in Iraq, Irgun chief David Raziel was killed by the Germans and his body was kept by the Iraqis until the early 1960s. Finally, with support from Indian forces, the British forced the Iraqis to surrender, and on May 30 the pro-German Iraqi officials escaped to Iran. Their successors signed the surrender documents.

From that point the Jews were in immediate danger. The surrender agreement stated that the British would enter Baghdad within two days. The Al-Fatwa religious movement saw a window of opportunity to incite the masses and blame the Jews for the military failure against the British. They marked the houses of the Jews in red and the next day, June 1, the mobs started rioting against the Jews – the first such riots ever in Iraq.

The rioters destroyed synagogues and murdered, raped and wounded people – the elderly and infants were not spared. The mob used all manner of weapons and also ran people over with vehicles. But some Jews were hid by their Muslim neighbors, who put themselves at great risk.

The massacre only ended when the British entered the city. The British actually knew about the pogrom a day earlier but did not try to prevent it; just like the local authorities, they preferred to let the masses vent their rage.

After the Farhud, the Iraqi authorities held an investigation, blamed nationalists, and even executed a few army officers involved in the incitement. Husseini, the mufti, was also mentioned in the investigation, and the German involvement was recognized over the years.

A monument in memory of the victims (actually, it was a mass grave – ed) was put up in Baghdad, but even so, the Farhud triggered the mass emigration of Iraq’s Jews. Between 1950 and 1952, Israel’s Operation Ezra and Nehemiah (1950-1952) brought some 120,000 people – 90 percent of Iraq’s Jews – to the young state.

Leave a Reply