With thanks: Michelle

Yeruham is a small, dusty town in Israel’s Negev desert. For decades, its population remained static as its residents fled at the earliest opportunity. The town was the setting for a film called Turn left at the End of the World. For many Israelis living in the centre of the country, Yeruham was the end of the world.

Now a documentary film about Yeruham, and development towns on Israel’s periphery, has ignited some lively debate. The film had its premiere at last year’s Docaviv film festival and was recently shown on Israel TV’s channel 13.

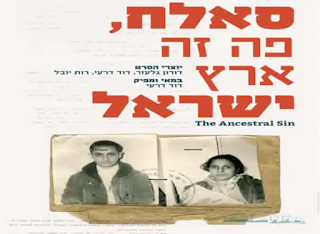

David Deri, who was born in Yeruham of Moroccan parents, made the film with Doron Glazer and Ruth Yuval. Known in its English version as The Ancestral Sin, the film’s Hebrew title, Salah, this is the Land of Israel echoes Salah Shabati, the character in Ephraim Kishon’s famous 1960s satire about the absorption of immigrants from Arab countries, but hints at the bitter disappointment that Salah would have felt on arrival in his new home. Israel was not the promised land: it was the end of the world.

David Deri was interviewed on Israel TV about his film here

and here

After 1956 and into the 1960s, the Israeli government implemented a policy called ‘From the ship to the village’. Thousands of refugees, arriving mainly from Morocco at the port of Haifa, were transported by the truckload through the night to new towns being built on Israel’s northern and southern borders. Israel’s leader, David Ben Gurion, called the strategy ‘obligatory discrimination.’

Stories of discrimination against Israel’s North African immigrants have been rife for decades, but what is new in Dery’s film is the assertion that official ‘protocols’ or directives existed to sanction any new immigrant who refused to get off the truck, or resisted resettlement in development towns like Yeruham. For instance they could be punished with fewer rations.

The film claims that Jewish Agency operatives who dispersed the refugees from Morocco despised them as ‘blacks’ and penniless lowlifes, putty in officialdom’s hands. Deri alleges that there was a policy to keep the Moroccans as far away from the centre as possible. Jewish refugees arriving from Poland under Gomulka at the same time, it is alleged, were given better treatment.

“It’s the truth, but it’s not the whole truth,’ says Avi Picard, a researcher who was consulted during the making of Deri’s film. Deri did not uncover any archive material that had not been in the public domain for 20 years or more, Picard claimed on his Facebook page. He criticised the film for faking some of the ‘protocols’ for the camera, misattributing quotes, and failing to convey the empathy which many Jewish Agency operatives felt for the refugees or give voice to their misgivings. The assertion that the state wanted to keep the refugees as far as possible from the centre so that nobody would see them was unfounded.

Picard himself still lives in Yeruham, whereas all but one of Deri’s ten siblings have deserted the town. He feels that a complex story – more cock-up than conspiracy – has been distorted for television but will now be treated as historical truth.

It is true that Israel pursued a policy of populating the periphery of the country for strategic regions. Ben Gurion himself tried to set an example by settling in a Negev kibbutz. The Polish Jews may not have been sent to development towns, but it is also true that Golda Meir ‘discriminated’ against sick or handicapped Jews, demanding that Gomulka’s Poland send only fit and healthy immigrants.

Enough material for more controversial documentaries in the pipeline.

Leave a Reply